A cut above

ROSIE MCGLADE enters the magical world of book and paper artist Sarah Morpeth at her rural studio in Northumberland National Park, and discovers a yearning to take up a new hobby . . .

It’s strange that our minds should turn to craft at Christmas, it being a hectic time of year and all, but come December, Kirsty Allsopp and Stacey Solomon have us convinced that Christmas isn’t Christmas without paper, glue and homemade cheer all round.

Paper cutting often features among the crafts guests on their TV programmes cover, where it generally looks a bit fiddly, repetitive, and possibly painful. Sarah Morpeth, on the other hand, a celebrated paper cut artist based in Northumberland, suddenly makes it look fun. A little bit compelling. And excitingly for the majority of us who can’t draw very well, actually do-able.

Sarah’s workshops in her converted barn in the village of Elsdon in the National Park guide people through six hours of design and cutting. Here, they enter into such a satisfying state of flow she sometimes has to remind them to breathe, and people who’ve never picked up a scalpel since school take home a beautiful silhouette picture they’ve made all by themselves in a box frame that subtly throws shadows on the paper behind it.

“Someone came here wanting to do a design with swallows and ended up with something absolutely beautiful,” Sarah says. “Another person did something on the theme of spring. She was a dentist. You really don’t have to be arty. The main thing is to get your head around what you’re taking away with your knife and what you’re leaving. It’s amazing how much you can cut away and the paper will still hold up.”

You also need a very sharp blade. “I use a surgical scalpel which you can buy in art shops,” Sarah says. “You want it to be so sharp that you don’t put need to put pressure on. The key is just to apply the same amount of pressure you would a pencil if you were drawing.”

Because of that it’s actually safer to work with a sharp blade, and while Sarah always has plasters to hand, they’re there mainly to wrap around scalpels because people tend to grip too hard. Only once has she ended up bleeding herself, when she was performing the simplest cut along the side of a ruler. A case of not paying attention.

She also went snow blind once, but that was after three solid weeks of work on a huge piece. There had been no break from her focus on the bright white paper that day, and: “I looked up and realised everything was a just a blur,” she says. It took a couple of days to recover.

“But it’s an incredibly relaxing and soothing art form. The tricky part is the design, but once I’ve helped people get that right and they start to cut, the atmosphere becomes very calm and meditative. You’re trying to get adults to play just for the sake of it, and I love that moment when they stop worrying about making mistakes and suddenly become fully absorbed.”

It sounds fabulous. “It is,” Sarah says. “And it’s cheap. You just need paper and a knife. I was very grateful to have support form the Ray Wind Community Benefit Fund to do up the studio. It has made a huge difference here.”

Sarah hasn’t always made a living cutting up paper. After studying classics at Oxford, she began her working life as a tax lawyer in London. “It was a bit like doing really complicated cryptic crosswords, we have such an archaic tax system in this country,” she reflects. “But when I got to my early 30s I realised I didn’t want to do it anymore.”

Her father’s sudden death brought her to a decision and she moved from London back to Elsdon (population 258 according to the 2011 census) and from sorting the taxes of Britain’s elite to pondering life as an artist. It’s the sort of brave step many admire, and few take. But Sarah had loved Elsdon from the day her family moved there when she was 17, having been born and raised to that point in Newcastle’s West Jesmond. Most teenage daughters (her younger sister was 15) would have been distraught at such a move, but Sarah loved it immediately. “It has always felt like home,” she says, adding that it suited what she describes as her naturally introvert nature.

It’s very beautiful. It has a pub, a church and a medieval Pele tower, and its houses gracefully encircle a large village green here in the midst of the wild, vast Redesdale countryside. “You do have to make yourself leave this place, as it can feel like the outside world doesn’t exist. You can go to Newcastle and feel gosh, this is overwhelming,” Sarah says.

She mentions her introvert personality several times in a two-hour stream of chatter, laughter and jolliness, which is quite a contrast, but then she pulls out her work and it becomes clear that most people would probably never guess half the hours of solitude, patience and diligence that have gone into it.

Her work station on a mezzanine floor above her studio looks like Edward Scissorhands has been in and left a frenzy of tiny paper shapes all over the floor – thousands and thousands of them. Sarah calls them her ‘snippets’ and sometimes one of them will work its way through the floorboards and drop through to the studio space below.

Originally, this was an old barn for storing hay. “My dad was an engineer and he had it full of metal cutting machinery because he use to build geological equipment,” Sarah says. “He had to be incredibly precise and focused on that precision. Just like you have to be with paper cutting.”

Her mother, for many years head of art at Sacred Heart High School in Fenham, Newcastle was an all-round artist and this was her studio. Then for many years she and Sarah worked here together. It took time and dedication to establish Sarah’s new life after giving up the law. Her first step was to enroll on an art foundation course at Newcastle College, where her fellow students were aged 18. “But I loved it. They just accepted me as one of them. When I did A Level art at school it was very traditional, but there we were doing textiles and ceramics, sculpture and fashion. I actually ended up doing a degree in embroidery at Manchester.”

It was an unusual course, which combined practical work with fine art and required students to submit a dissertation that took them beyond traditional embroidery. Sarah found she loved stitching into paper and she became fascinated with book binding.

“I came out of it making books,” she says. “All the academic stuff I’d done in the past was so prescribed, but there we were allowed to pick something visual to research, and it could be anything you wanted. It was such an interesting opportunity.”

She had long been fascinated with the film and art of the 1940s, particularly in light of wartime censorship and its influence on the work of that period. Her favourite film then remains her favourite now to the point of obsession, she happily acknowledges, and she has written, cut up, tailored and re-imagined every word and theme from it, quite literally.

I Know Where I’m Going, starring Wendy Hiller and Roger Livesey, is a 1945 romantic comedy directed and written by the maverick film-making duo Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Set on the Scottish island of Mull and shot of course in black and white, it tells the tale of a young woman on her way to marry a rich industrialist but for whom destiny has other plans. Mystical, beautiful, and romantic, it is the favourite film of many, including the Oscar-winning director Martin Scorsese (who recently made a documentary about it) and the equally acclaimed actor Tilda Swinton.

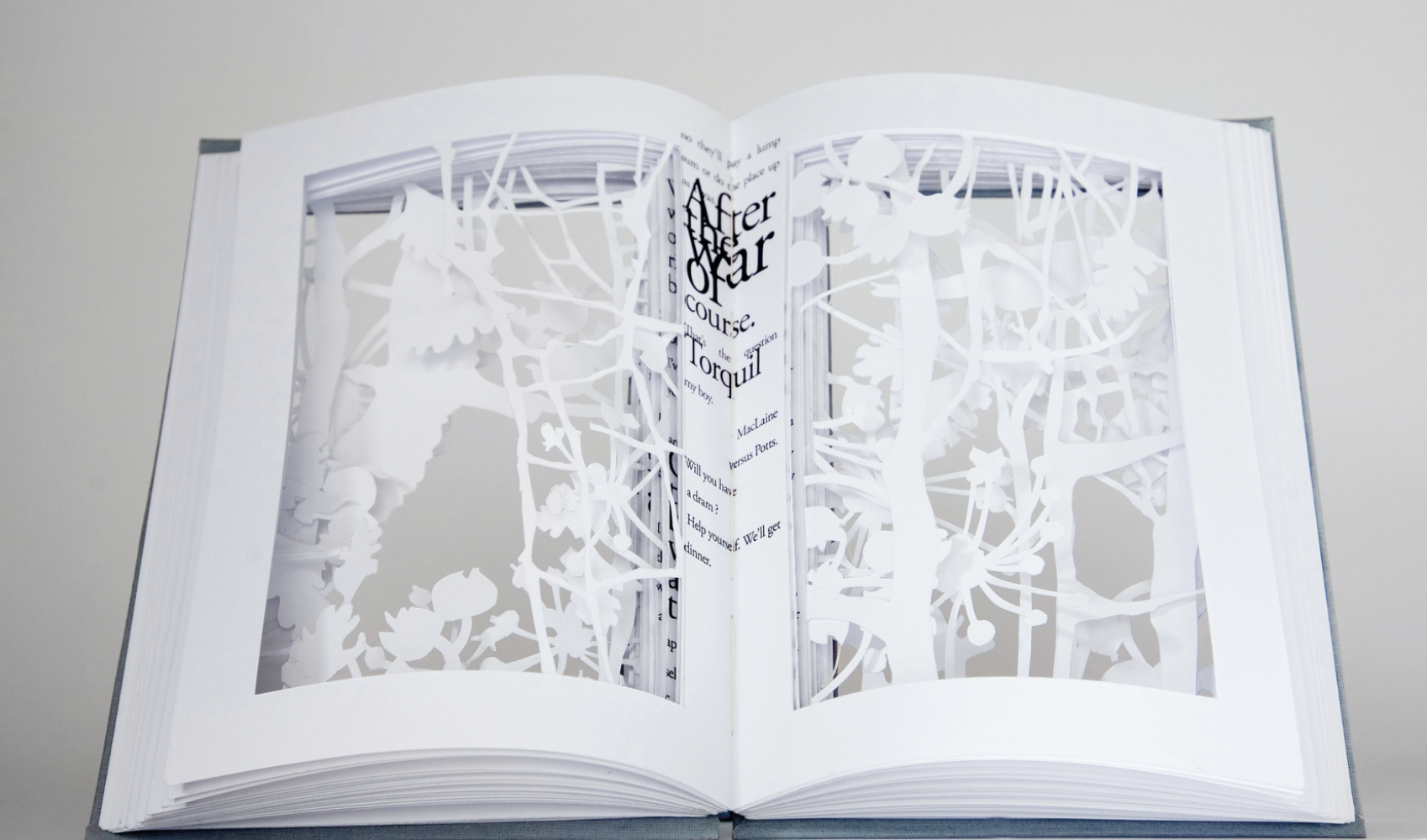

Sarah has made books focusing on each of the film’s five main characters, and other books dedicated to its locations and themes. It does sound a little obsessive at first, but then she brings the books out and you see that each is a beautiful and stirring work of art. The first she shows me is for Torquil MacNeil, the young Navy officer with whom the film’s female lead Joan falls in love, and features a circle of apparently burnt cut-out trees menaced by flying crows suspended on wires. All Torquil’s lines from the film are printed on it, and its circular design, with its central binding and pages fanning out around it, reflects the famed Corryvreckan Whirlpool scene from the film.

“There’s a marriage of form and content in an artist’s book that I find really interesting,” Sarah says. If you’re not in the know, an artist’s book is generally interactive, portable, movable and easily shared. Some artist’s books challenge the conventional book format and become sculptural objects. There are festivals that celebrate the genre, attracting what Sarah describes as a small, happy niche of people.

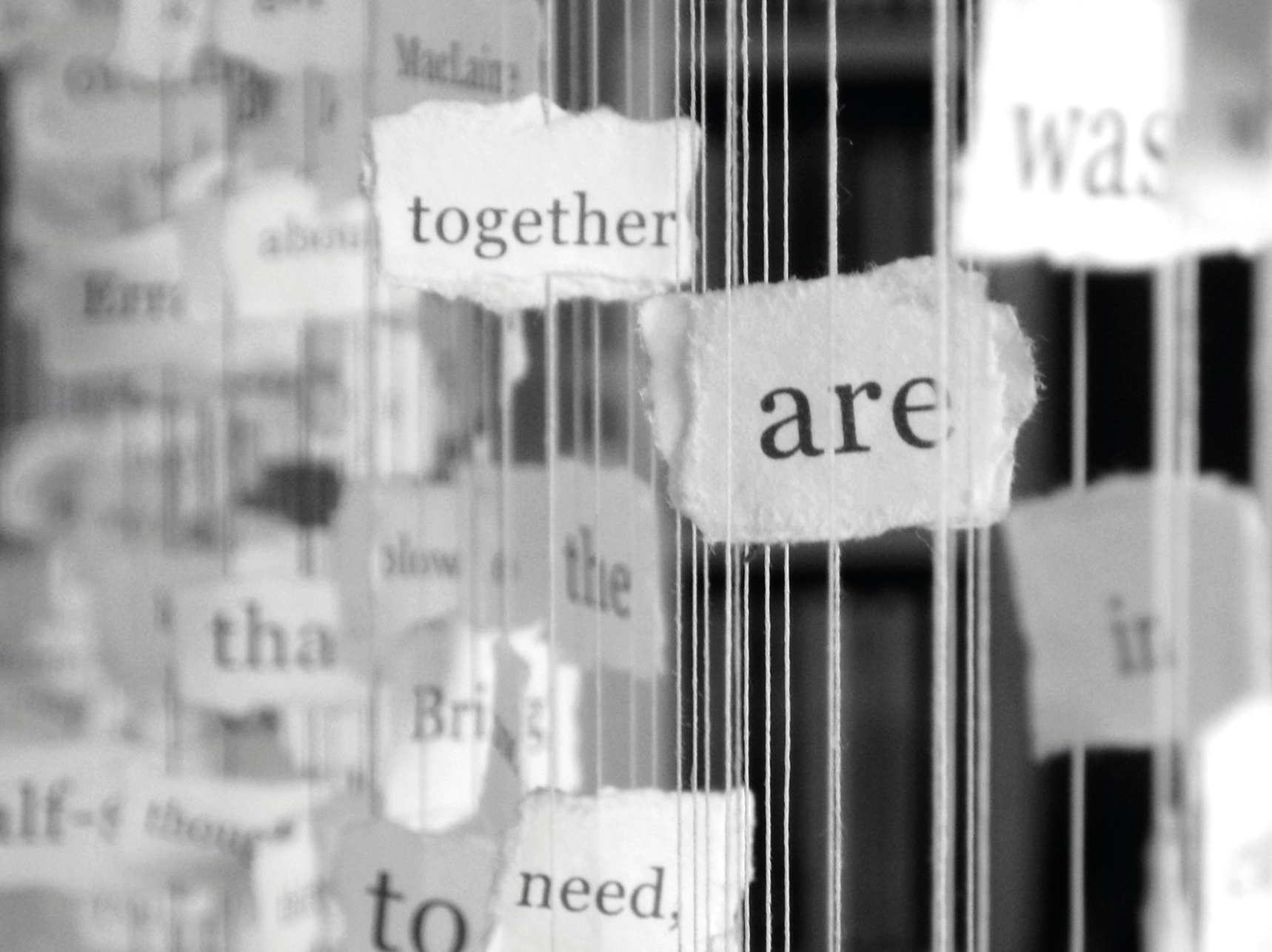

Sarah’s book for Joan, the heroine in the film, also features all her lines. It is more traditional in form, except that Sarah has torn each word from the next, run thread through each of them, and pulled them down in a long stream, reflecting the waterfall in the film. It kind of defeats your notion of what a book is, Sarah explains, and it is incredibly stirring.

There is a concertinaed tunnel book representing a location in the film – the sort of bottle dungeon you sometimes find in castles in Scotland, where all you see, standing at the bottom, is a little circle of light at the top – and there are two books focusing on the film’s other female main character, Catriona.

The work featured in a gallery residency on the island of Mull itself, and it is these bigger, grander conceptual pieces that fuel the inspiration for the smaller pieces Sarah makes for sale at a range of price points that begin with affordable card sets.

Her books and paper cutting have a lovely crossover. “They’re a magical transformation of an A4 piece of paper. You can do something simple just by folding it in half and cutting and it becomes a magical little world. That’s the kind of thing we do in my book-making workshops. I love it,” she says, showing me a simple pop-up book with hares leaping from each little page; the sort of thing people on her workshops might make in a day. It’s charming and is a popular format she constantly returns to.

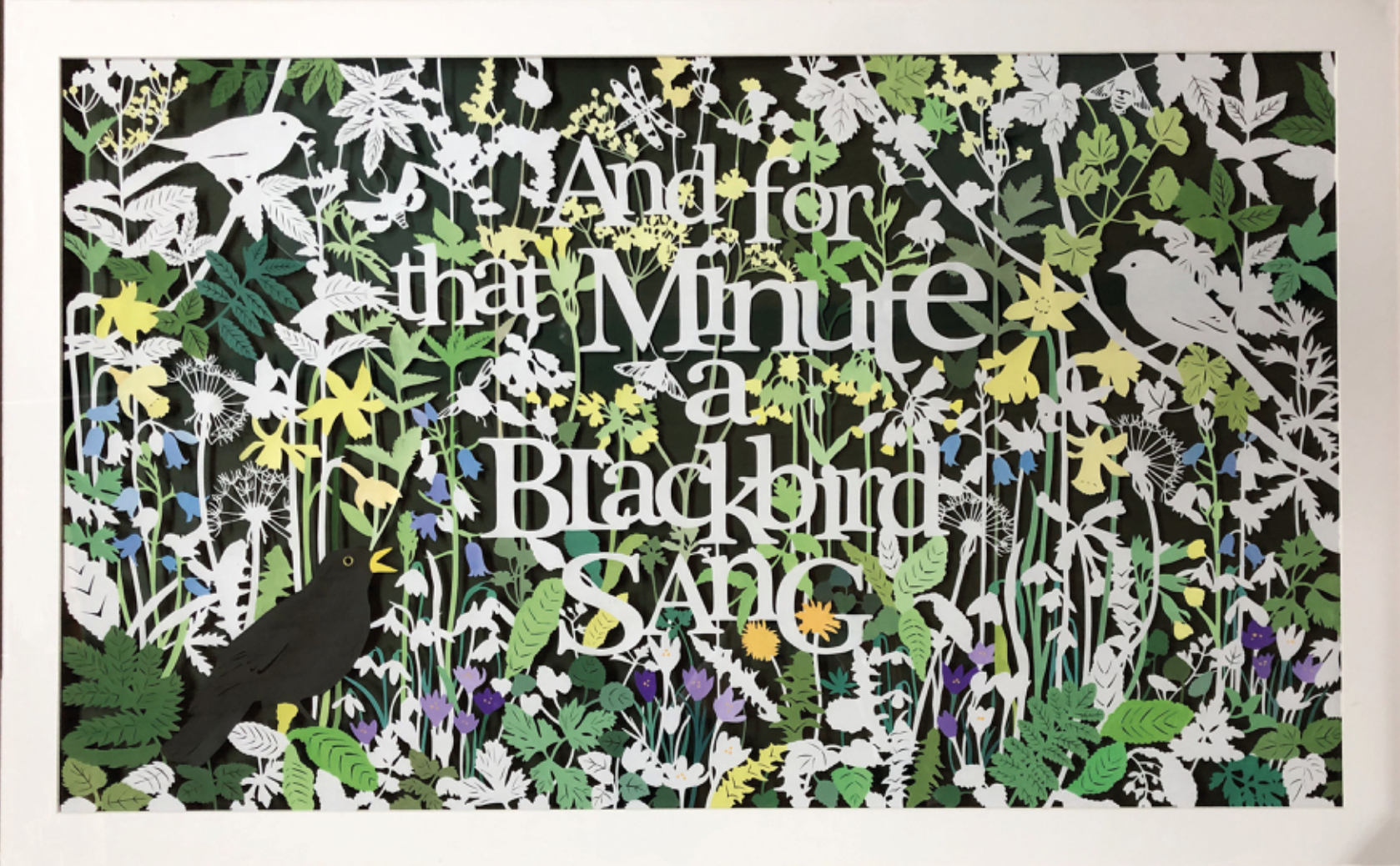

There’s a hedgerow piece made from layers of paper that create a 3D world in which you can see a little wren hiding in tangled branches. It’s beautiful, the result of a commission from the Inspired By gallery in North Yorkshire National Park, and Sarah makes a simpler version for sale.

Another major project was for a residency at the Georgian Theatre Royal in Richmond where, inspired by the typefaces on the posters that celebrated its opening plays in 1788, she made huge pieces of lettered works bringing back to life the first words spoken on the stage. It is one of these that caused that episode of snow blindness.

“Lettering is a nightmare,” she concedes. “You can’t make a mistake because it’s really obvious. With plants, flowers and leaves and so on you can change the composition if you go wrong.” Unfortunately, you can’t stick anything back on, and everything is drawn up before she begins on a composition.

Sarah was deeply affected by her mother’s death, but her art helped her to heal. “During lockdown a few years later I just felt so lucky to be here in this beautiful place,” she says of that time. “The weather was lovely and the hedgerows were full of wildflowers. I would walk the dogs and draw everything I was seeing, then come back and just make paper cuts. Grieving is a long process. It’s not just something you can stop because you don’t want to be in it, but lockdown allowed me to throw myself into my art again. Nature is such a healing thing.”

To book a paper cutting or book making workshop with Sarah at Elsdon or at The Biscuit Factory in Newcastle, go to

www.sarahmorpeth.com where you can also purchase her work, including cards, paper cut kits, garlands and artwork, which is also available to buy from Number One Gallery at Kirkharle, and Milkhope Creatives, Blagdon. Sarah takes on commissions for which she starts with a client’s favourite piece of text and imagery and incorporates them into a paper cut