Watching the clock

Preston Tower

This week, Charlie is mostly watching the clock…

Sardines is a variation of hide-and-seek where players join their target in their hiding spot, eventually becoming cramped together like sardines in a tin. Likewise, in the British Isles, which are very old, objects have accumulated cheek-by-jowl over the centuries, again like sardines. This has happened as man and nature have deposited, placed or lost them. Thus, wherever you turn, if you keep your eyes open, an ear to the ground, and your nose in the air, you will never be far away from something to delight you for a moment, often a lifetime.

During my life I have been lucky enough to come across some amazing objects that have not always been well-known. Take the animals of Hexham Abbey. Here I had one of those strange thoughts that often come into my mind. There are interesting living creatures in the grounds of the Abbey, but what of the bestiary of creatures on the inside; those made of stone, cloth, glass or wood? Well, with the help of polymath Hugh Dixon, I found all the usual subjects like doves, lambs that never make sheepdom, and fish, and beyond them a menagerie of creatures from monkeys to wyverns to a small dog peeing on a lady’s shoe.

This discovery of objects which lie in plain sight but are not thought of or discussed got me thinking. What else might I know about that quietly goes about its business without raising so much as an eyebrow? Well, I have quite a list, which I’m going to document in some of my columns over the next few editions. First, to Preston Tower, home of my great friend Harry Baker-Cresswell. Harry’s family have been living there or thereabouts for more than 200 years. The house is a beauty with a delightful garden where there is a special surprise. For only 100 yards from Harry’s front door is a magnificent pele tower called Preston Tower; the building that gives Harry’s house its name.

Those not from Northumberland might wonder what a pele tower is. Well, in 1392 it was a tower to protect your family, your stock and perhaps your cats (the latter definitely if you are the current Mrs Baker-Cresswell) from marauders from the north (Scotland, as some call it), though these reivers were not exclusively of Scottish heritage and could come from Cumbria or just over the fields. The only Bennetts I know of from Scotland were such folk. I’ve always known we’ve been farming for a long time, and I guess stealing somebody else’s cattle saved a load of bother. The origins of our present-day mantra of common-sense farming, perhaps?

Anyway, Preston Tower was constructed between 1392 and 1399, during a time of ongoing conflict between England and Scotland. By the early 15th century, it was one of 78 similar structures in Northumberland. Over the years, it has been owned by various individuals, including one Sir Guishcard Harbottle (what a name . . .) who died fighting against forces led by James IV at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 – an event that paved the way for Mary, Queen of Scots’ ascension to the Scottish throne.

I could go on about the history of the tower, but I won’t as it isn’t the object I want to tell you about. For as you wander around what is left of it you notice distinctive clock faces. Just seeing them made me proud to be from these islands. Why? Well, because I revel in our eccentricity. It turns out that in 1864, wandering around his garden and looking up at the tower, Harry’s relation Henry Robert Baker-Cresswell had a thought: “What that tower needs is a clock.” Now this might have been more obvious to him than me thinking, “Hmmm, those antlers would look good strapped to the front of my Land Rover” (the local constabulary soon put a stop to that idea), the reason being that Henry was, like many of his generation, an engineering genius.

Being such a bright spark, he didn’t go down to the clockmaker in Newcastle, of which there were many, and ask them to make his clock. No, he decided to build it himself. Scratching his head over a glass of sherry and a wafer-thin biscuit one evening, (or it might have been the third glass – history doesn’t relate), his mind leapt to the flat-bed type of clock perfected by Lord Grimthorpe. This was an inspired thought as the most famous clock of this design is the Great Clock of Westminster, housed in the clock tower of the Palace of Westminster, home of the great bell Big Ben. “I know, let’s have a mini-Big Ben in the garden!” he might have declared. “Yes, dear,” his long-suffering wife might have replied.

The clock workings

One Sunday afternoon Harry kindly agreed to take Mrs Bennett and me to see the clock. Climbing the wooden stairs of the tower, the first evidence you might be in the presence of a venerable old timepiece is a pair of huge cylindrical stone weights. These are beautifully hewn of what I’d guess is sandstone, one weighing 200kg the other 50kg. We’ll come to them in a moment, because climbing further past the arrow slits (where people might have cried, “bother, the Armstrongs are popping over and I don’t think it’s for a cup of mead . . .”), eventually we came to the clock room.

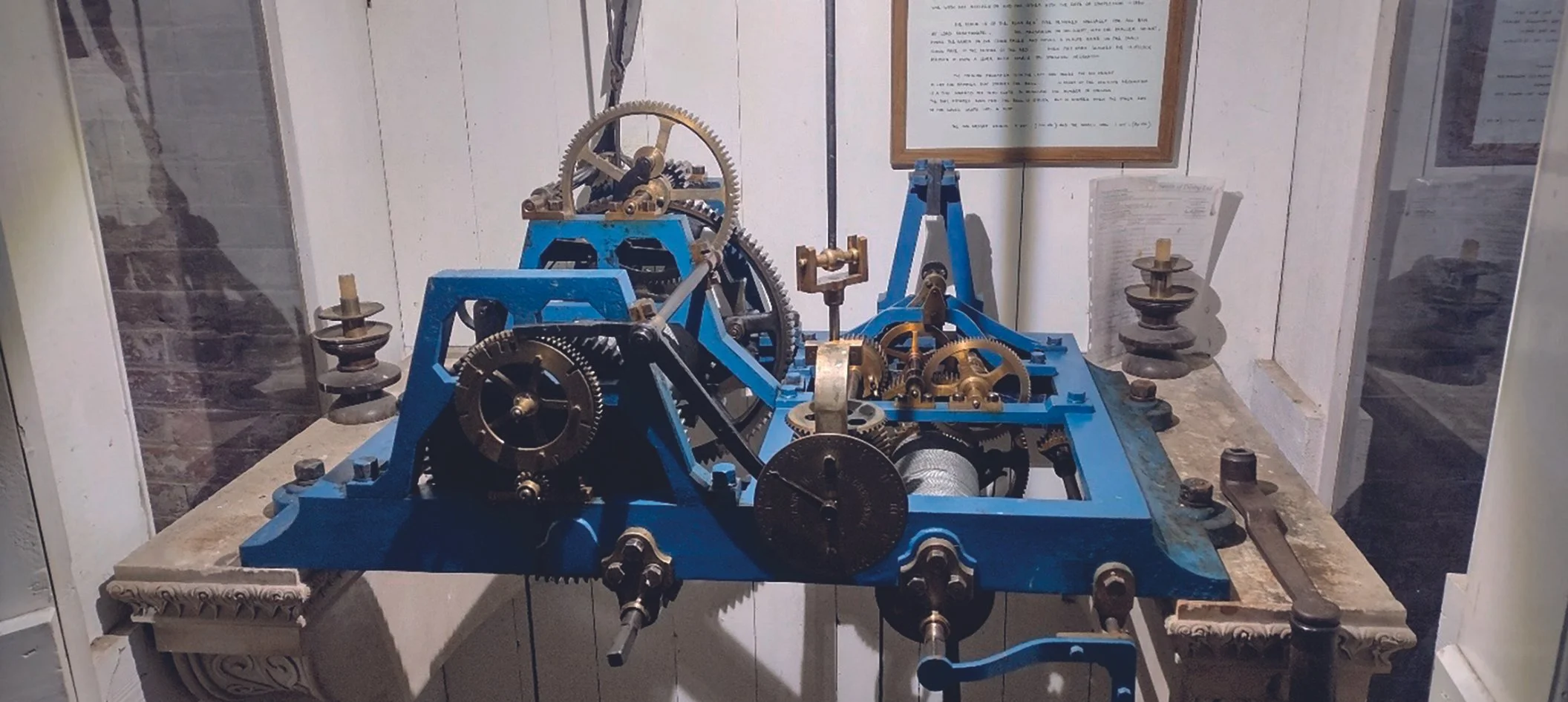

Now, this timepiece is not like the one you might have on your mantelpiece. What you see here is the clock mechanism, from which long rods turn the hands on the clock faces outside and operate the bell. It is a beautiful piece of engineering. It sits in a glass case and rests upon ornate stone brackets (found in the garden, naturally). The clock is a multitude of beautifully organised brass cogs, flywheels and thingummy-bobs moving at varying speeds that ultimately transfer their labour to telling almost perfect time.

Back to the weights. They power the clock and allow the striking mechanism to strike the big bell. They are lifted by winding the clock which allows it to run for a maximum 48 hours. Now we are back in the world of the eccentric English. For you see, Harry is not only married to the lovely Joey, but he is also married to his clock. Every day he climbs up to the clock room and 45 winds later the weights are high enough to keep the good people of Chathill and beyond in the knowledge of the correct time as the clock strikes on the hour. That might sound easy, but one wind is like starting a Sopwith Camel. Hence, Harry is loath to let the clock run for more than two days as he must then wind those weights over 90ft. A good 45ft is enough for anyone’s pre-breakfast workout, after all . . .

I said the weights help the striking mechanism. With this in mind, I enquired about the bell. Harry took us up to the roof of the tower, from which you can see for miles around (and presumably have an even earlier knowledge of those pesky Armstrongs). In a corner of the roof is a neat square turret in which lives a huge bronze bell. Harry kept my attention with stories of the view, more history and even a passing gull, thus cleverly keeping me from looking at my watch before the bell struck. When it did sound, it was like a cannon going off and I nearly leapt out of my skin, turning to find Harry and Mrs Bennett bent over double, howling with laughter.

Having recovered my marbles, we made our way back down to terra firma. What a treat. An afternoon with one of our favourite people in the world, a trip around Northumberland’s Big Ben, and the added bonus of being unable to hear the jobs Mrs Bennett had in mind for me when we got home. I suggest you go and take a look for yourself – the details are on the website:

www.prestontower.co.uk

Charlie Bennett is co-owner of Middleton North near Wallington, where he works to support existing wildlife and attract new species alongside sustainable stock farming designed to add to the diversity of wildlife in the area. For information, visit: www.middleton-north.co.uk To enquire about volunteering, email charlie.bennett@middleton-north.co.uk

• Charlie’s new book, Climbing Stiles, A Wander Through the Countryside & Beyond, is available in hardback priced £14.99 at bookshops and online at: www.charliebennettauthor.co.uk

The vast clock weights