For the birds

A detail of the portrait of WH Hudson by Frank Brooks which hangs at RSPB HQ in Sandy, Bedfordshire

Conor Mark Jameson, author of a biography of the campaigning conservationist and supporter of the founders of the RSPB, WH Hudson (1841-1922), explores this fascinating man’s love of Northumberland and his long friendship with Viscount Grey of Fallodon

By the time he passed away in 1922, WH Hudson was a household name. The author and conservationist had published 24 books, had Hollywood bidding for movie rights to his work, and in 1925 a chunk of Hyde Park was dedicated to his memory, complete with a sculpture unveiled by prime minister Stanley Baldwin.

The son of Americans who migrated to Argentina in the 1830s to try their hand at sheep farming, Hudson arrived in England in 1874. By now he was in his early 30s, largely unschooled and had little money. But a decade or so of obscurity was followed by a slow but steady rise in his fortunes in parallel with his association with the birth of the conservation movement.

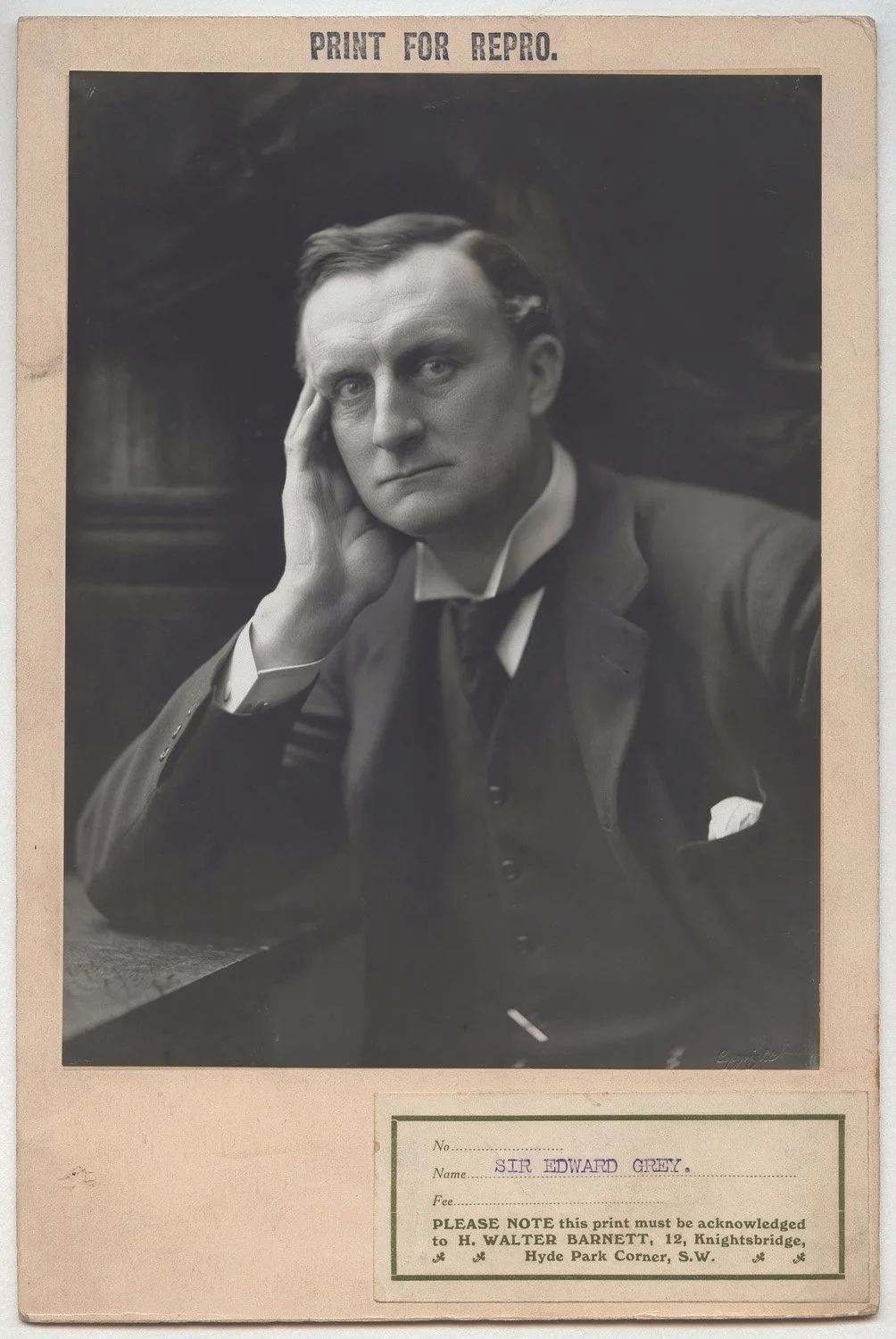

He was the only man in the room when groups of women gathered in London (and in Manchester) in 1889 to form the Society for the Protection of Birds. Their focus was to end the vast global trade in wild bird plumage for fashion, which was no mean ambition. Through this, Hudson met another rising star – the Liberal politician Sir Edward Grey, MP for Berwick-upon-Tweed. Grey recognised the greatness of Hudson’s writing, particularly about nature, and became a vice-president of ‘The Bird Society’, as Hudson liked to call it.

Hudson was briefly its chairman, and in late June 1894 he embarked on birding expeditions with his female co-founders. They travelled first to Norfolk, then to Bridlington by boat, then Flamborough Head before going on to Sunderland, Bamburgh and the Farne Islands. New protection laws had been brought in to protect the nesting seabirds from over-exploitation and Hudson’s group enjoyed “a good week” checking on progress, spotting “tens of thousands of guillemots, puffins, razorbills, cormorants, gulls, terns.”

Sir Edward and Lady Dorothy Grey, on bicycle and trailer at Fallodon estate, to which Hudson was invited. ‘There will be a horse to ride about the moors, he says, and that is a great temptation.’ (Image courtesy of Adrian Graves)

Not long after, in a letter written in September 1894, Hudson told fellow author George Gissing that he had been invited to visit Lord Grey’s Fallodon estate in Northumberland, adding: “There will be a horse to ride about the moors, he [Grey]says, and that is a great temptation.”

Having become involved with the Society for the Protection of Birds the previous year, Grey was keen to become better acquainted with his new friend and colleague. Lady Dorothy Grey was also a great fan of Hudson’s writing, and Hudson was struck by the unusual depth of her connection to nature.

Hudson may have stepped off the train and walked to the Greys’ front door, as it had been made a condition of the East Coast mainline rail track being laid across the Fallodon estate that any passengers wishing to alight there could do so.

Lord Grey’s growing esteem for Hudson is reflected in the assistance he gave him to secure British citizenship, and later a civil list pension of £150 per year following his 60th birthday in 1901. Thereafter, Hudson’s late-life rise was meteoric and his output prolific. ‘The Bird Society’ was thriving in parallel.

Grey also did Hudson the honour of giving him the keys to his fishing cottage on the river Itchen in Hampshire, providing a rare opportunity for Hudson to spend a whole summer with his wife Emily, free of the confines of their London home.

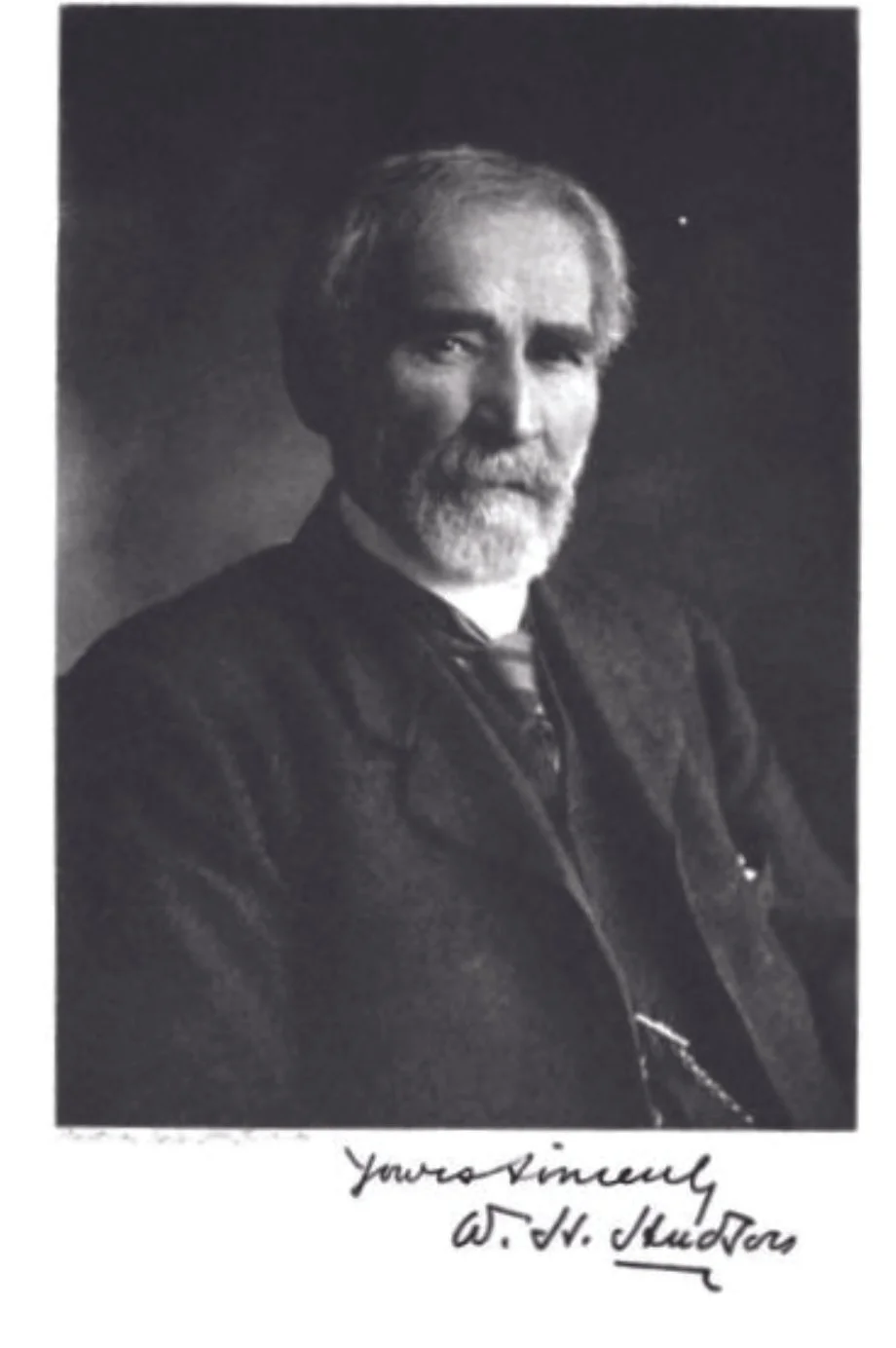

WH Hudson photographed for the frontispiece of his novel Far Away and Long Ago, EP Dutton & Co, New York

Early in 1906, news of a terrible accident reached the Hudson household from the Greys’ Northumberland estate. Lady Dorothy had sustained a serious head injury after falling from a carriage. Her husband was interrupted during a meeting at Westminster to be given the news and he rushed north to be by Dorothy’s bedside, where she remained unconscious for several days.

Hudson feared the worst, as he confided in a letter: “The last two days I have been miserably anxious about poor Lady Dorothy. Her death would be a frightful blow to him… No two that I have ever known were more like one.” Despite all efforts to revive her, Lady Dorothy never regained consciousness. “She was a glorious woman,” Hudson wrote to friends.

Bereaved, Edward Grey threw himself into his work with increased vigour. He would hold the post of foreign secretary for a decade, and in August 1914, with his famous ‘lamps going out’ speech, he announced to the nation that Britain was at war. Two years in, exhausted and partially blind with overwork, Grey finally stepped down. He accepted a peerage and became Viscount Grey, having been the longest continuously serving foreign secretary. Asquith’s ministry collapsed at the end of the year and Lloyd George became prime minister, leaving Grey in opposition from his seat in the House of Lords.

Sir Edward Grey

Hudson and Grey’s war years had their share of personal tragedy, too. Grey would receive news from the Western Front that his nephew had been killed, while close friends also lost their lives. In 1917, Grey’s house on the Fallodon estate caught fire, and part of it was badly damaged. “It is difficult in these dark days not to become disheartened and discouraged,” Grey wrote to his sister. “I find that what helps me most is watching the stability of nature and the orderly procession of the seasons.”

Grey was fond of sitting in his study at Fallodon, red squirrels appearing at the window and venturing onto his desk to steal a nut from his outstretched hand before darting back to the ledge. He could see them, but not well, and dictated a note to Hudson about his predicament. “Have just had a long letter from Lord Grey about his blindness,” Hudson wrote. “He can’t read at all; he says he’s having my book read to him. He sees just well enough to walk and cycle, but everything appears like a blurred photograph. He can fish.” The book being read to Grey was Far Away and Long Ago, Hudson’s vivid memoir of his Pampas childhood.

Dorothy Grey (courtesy of Adrian Graves)

Hudson retained his impressions of Northumberland until late in life. Writing in August 1919 to Mary Trevelyan, daughter of the historian George Macauley Trevelyan, and sister of Charles, George and Robert, known affectionately as ‘The Trevvies’, he said: “I wish I could go once every year to the Northumberland coast by the Farnes and Holy Island.”

He makes a further reference to Northumberland in response to a letter of 1920 from Gemma Creighton, daughter of his friends Bishop and Louise Creighton. Her 12-page letter describing a holiday in the hills prompted another bout of Hudson nostalgia. “A mountainous district seen at a distance always produces the effect of a land of mystery and enchantment and fills one with the desire to explore it and the Cheviots – always seen far off – stirred me strongly in that way.” Another Mary Trevelyan letter soon after, “revived memories of the glimpses I have had of all that wild north land of hill and moor and the longing to spend months in rambling in it.”

In late 1921, Mary Trevelyan, now 17, wrote to him again, describing long bicycle rides and walks. He replied in April 1922, saying that her words had given him an ‘intolerable craving’ to revisit the moors and coast of Northumberland. It was a forlorn, belated hope, as he had just four months to live. That same month, the Plumage Act finally became law – a fitting finale to Hudson’s campaigning life.

That summer, conservationists from around the world gathered in London to form a global alliance for bird protection that endures to this day. While Hudson took a back seat, Viscount Grey was present. Their declaration of principles was clear: “By united action, we should be able to accomplish more than organisations working individually in combating dangers to birdlife.”

Hudson knew better than most that saving nature must be an international movement. For birds know no boundaries, much like the intrepid Hudson himself.

Finding WH Hudson, The Writer Who Came to Britain to Save the Birds, by Conor Mark Jameson, published by Pelagic, is £17.99 at

www.pelagicpublishing.com/products/finding-w-h-hudson