Bridging centuries

Lambley Viaduct

ANTHONY TOOLE enjoys a small slice of South Tyneside history with a walk taking in spectacular Lambley Viaduct, Featherstone Castle, and the site of a World War II POW camp

Despite the cold breeze, there were unmistakable signs of the coming spring. Trees that appeared leafless were opening their first buds, while the gorse was in full blossom. A curlew called from across the river and a pair of piping oystercatchers marked out their nesting patch amid the gravel of a quite large mid-stream island. The surrounding waters ensured that the oystercatchers’ eggs would be safe from predation by a fox, but perhaps not from an opportunist otter. Elsewhere, a dipper bobbed on a boulder before diving into the current, reappearing a few seconds later to claim a different rock from which to repeat the procedure.

Half an hour earlier, we had left the car at the parking area near the Wallace Arms at Rowfoot, some 2 miles south-west of Haltwhistle. We followed the road, unperturbed by traffic, gently uphill into the wind, then down again, past tall conifers among which a sign asked us to watch out for red squirrels. Lambs played in the fields and a roadside fence was festooned with the mummified carcasses of more than 50 moles. A tree stump displayed last autumn’s luxuriant growth of fungus.

We avoided a loop in the road by means of a footpath across a field, which brought us to a wooden bridge over the South Tyne. We stayed on the east bank of the river, the footpath taking us past Featherstone Castle, the origins of which lie in an 11th century manor house built by the Featherstonehaugh family. Its proximity to southern Scotland meant that it was involved in many of the border conflicts of that era, and an adjoining pele tower was added in the 14th century. 300 years later, the house was enlarged to its present size. Having changed ownership several times, it enjoyed a period as a boys’ preparatory school during the mid-20th century, after which it became a conference, wedding and activity centre, and continues to function as such today.

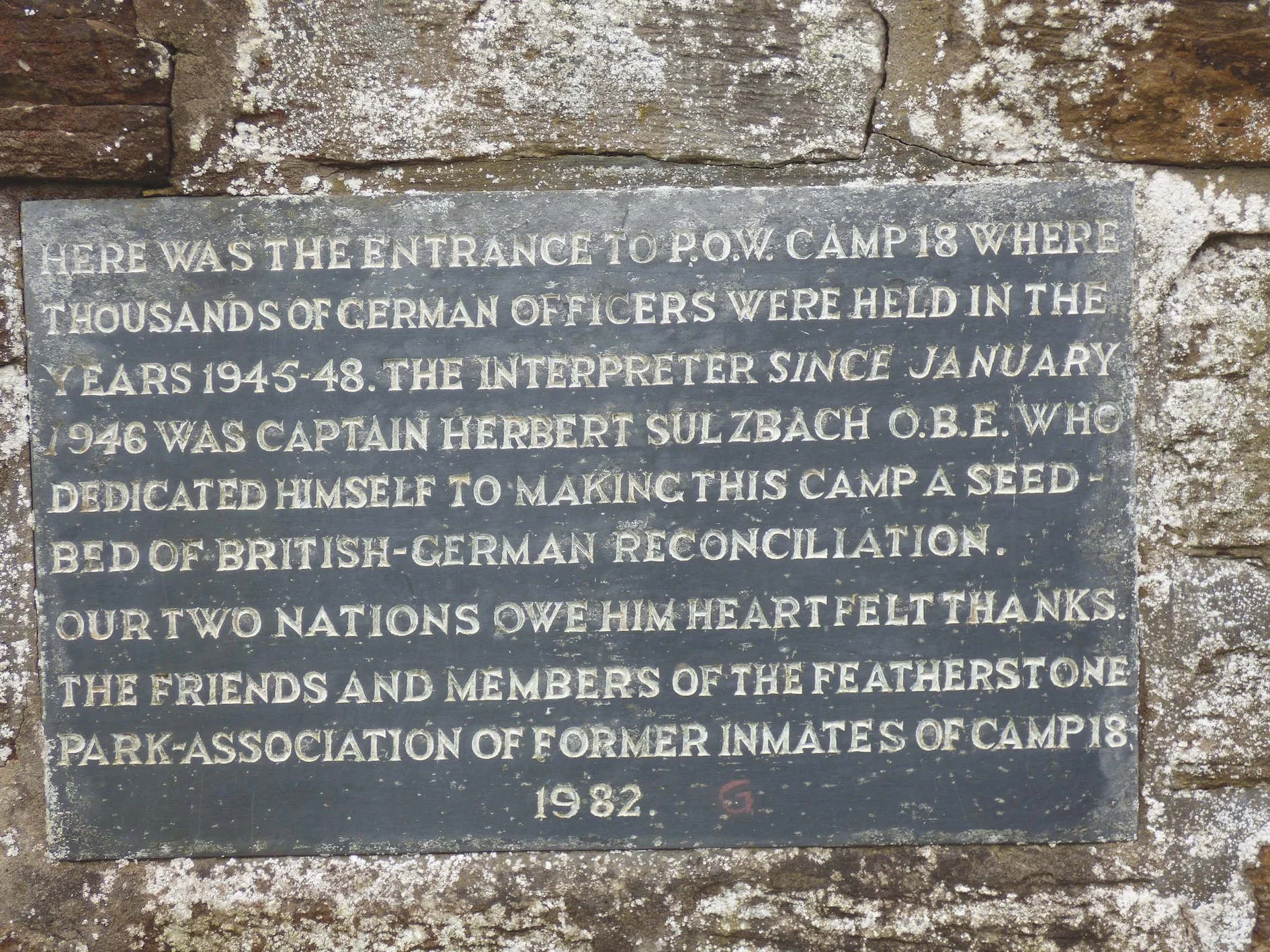

Accompanied by further heralds of spring in the calls of a willow warbler and chiff-chaff, we came to the stone-built relics of a World War II prisoner-of war facility, known as Camp 18, which from 1945 to 1948 had catered for some 7,000 German officers. Though the standing buildings were few, the numerous crumbled walls and the grass rectangles, which even after many decades remained discoloured, testified to the huge area once occupied by the camp. A tall pillar, all that was left of the entrance gate, bore a plaque dedicated to the memory of Captain Herbert Sulzbach, a camp interpreter who had worked hard, and with considerable success, for British-German reconciliation while the soldiers awaited repatriation. Parts of the road that still ran along what was the edge of the camp had, over the years, been washed away by the meanderings of the river.

The dedication on the pillar

A few hundred metres beyond the camp, we crossed a road linking the villages of Coanwood and Lambley to the continuation track that skirted what appeared to be an area of landslip. The hillside was colonised by celandines, coltsfoot, small clumps of primroses and a solitary wild strawberry flower. A wooden bridge crossed over a thin tributary stream, the banks of which were overgrown with wood anemones and more celandines. We stepped over a stile beside a fishermen’s shelter and continued to our first sighting of the huge Lambley Viaduct. We crossed a footbridge to the west bank of the river, and ascended a set of steps up the steep, wooded hillside to the southern end of the viaduct. Here, we stopped for lunch.

The viaduct was opened in 1852 as part of the Alston-Haltwhistle railway, carrying lead and zinc ores, coal and limestone from the mines and quarries of the North Pennines orefield. On reaching Haltwhistle, the minerals were transferred to wagons on the Carlisle-Newcastle line for further transport. The line closed in 1976 and the viaduct fell into disrepair. It was restored 20 years later and is now a Grade II listed structure. The southern end, which would have given access to Lambley Station and village, is now blocked.

The nine 17-metre-wide arches of the bridge carry what is now a well-surfaced track for 260 metres over the gorge at a height of 33 metres, with superb views over the South Tyne. To one side, the river runs north in an almost straight line through woods that reach down almost into the water, and toward a distance marked by the high ground beyond the Roman wall. To the other, it flows from the south, then turns in a broad loop past a large, scoured area of gravel and beneath the viaduct, the view this time limited by the rise of the hillside fields to the east. From this height, the trees that had seemed so bare as we passed them acquired something of spring greenery.

From the northern end of the viaduct, we joined the wooded track beyond, which though roughly surfaced was still good, except for a few places that held water left by the spring rains. After ½ mile, we reached a raised platform covered with mats of forget-me-nots, which is all that remains of Coanwood Station. We again crossed the Coanwood-Lambley road, then through a car park. One side of the track was now lined with the brick walls of one-time buildings. Nature, however, had taken over, and we passed mature trees, a mixture of deciduous and very tall Scots pines. The slopes of the railway cuttings were carpeted with wood anemones, a dense layer of poisonous dog’s mercury and scatterings of raspberry bushes and pussy willows. And from breaks in the vegetation, we were able to look down onto the earlier part of our walk.

We passed beneath a former railway bridge and after a short distance arrived back at our starting point. Our 5 mile excursion, which had been full of historical interest, had occupied us for a leisurely three hours.