Death on St Oswin’s eve

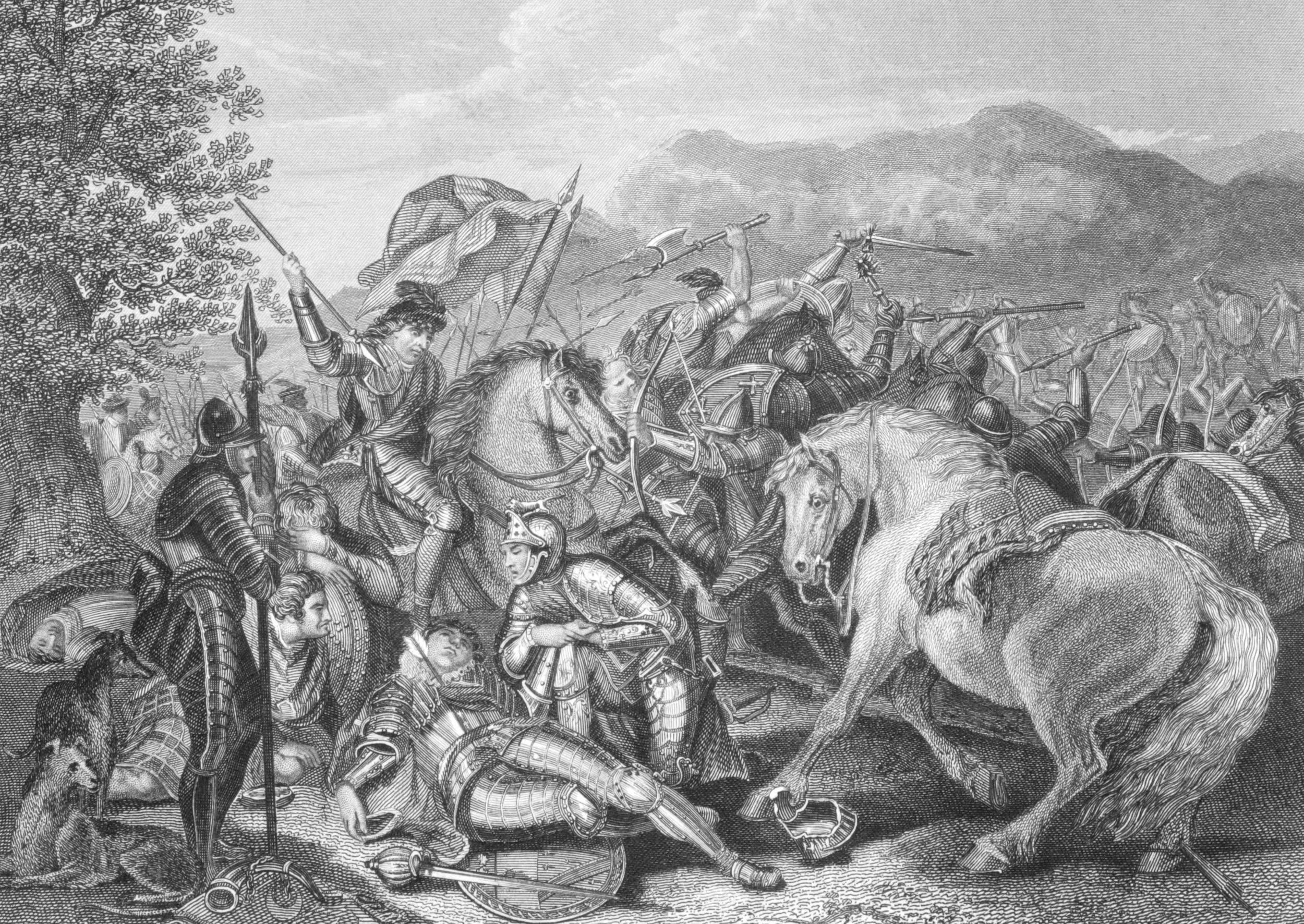

The Battle of Otterburn, by Georgios Kollidas

On the occasion of its anniversary, JOHN SADLER and BEV PALIN recount the Battle of Otterburn, August 1388, and delve into the many theories that surround the experience of the Scots led by the doomed Earl Douglas, and the English led by Harry Hotspur

On a wild, windy day in August 1988 on the site of the Battle of Otterburn (depending whose account you believe – there are conflicting theories) I was part of a 600th anniversary re-enactment of the battle. To add spice (and the possibility of real bloodshed) the MoD furnished the day with a company each of English and Scottish trainee NCOs with a cadre of instructors.

Thank God the weapons were wooden, as the Scots took the whole business so seriously that if anyone doubted they’d won first time around, now it would be definite. This was well-drilled, coordinated fury, NCOs bellowing themselves hoarse as they urged their charges on to closer drill and ever more focused bloodlust. In both they succeeded admirably, and we reenactors were totally outclassed.

Though not a major fight, the intensity of the battle and the balladry it inspired guaranteed it lasting fame. And though he lost, Harry Percy (‘Hotspur’ the sobriquet awarded by his Scottish enemies) was able to fuel his own legend. Medieval chronicler Jean Froissart (primary authority for this battle) records that while Harry was beaten, his ransom (7,000 marks) was soon raised and paid over and he suffered no fallout from the defeat. Ironically, 14 years later at Homildon Hill he’d be fighting alongside his nemesis at Otterburn – George Dunbar, Earl of March.

Chroniclers broadly agree the facts of the Scottish invasion, which was more a large-scale raid led by March and James, 2nd Earl Douglas, intended to draw English attention away from a serious thrust down the west flank and into Cumberland. Striking fast and hard, the Scots blitzed through Northumberland and into Durham, withdrawing just as rapidly.

There was likely some skirmishing outside the walls of Newcastle and legend asserts Douglas grabbed Percy’s pennon from his lance tip, a chivalric loss of face, and dared Hotspur to come after him and win it back. We can choose if we believe this or not, but we can accept that Percy, realising he was facing far fewer numbers than anticipated, decided to seize the initiative the Scots had so far monopolised and give chase.

Dunbar didn’t slacken his own momentum as his column, burdened with stolen cattle, hurried towards the safety of the border line. These Scottish raiders or ‘hobilers’ (named after their light, fast horses) were able to travel rapidly despite trailing so much four-footed loot.

It is thought that Hotspur’s force, at 6,000-7,000, was substantively larger by some two to one. They covered 32 miles from Newcastle to Otterburn that afternoon, which is impressive, though most would be mounted on hobbys like the Scots and at 7-8mph could probably cover the distance in 5-6 hours. If they marched at noon they would be approaching Otterburn by late afternoon/early evening, the hour of vespers, with time to deliver a knockout blow before dusk around 9pm.

March had halted his doubtless tired army just beyond Otterburn and spent three rather pointless days trying to take the castle (now a hotel). He might be confident, but Dunbar was cautious and would have plenty of scouts out. For Hotspur to risk an immediate assault and avoid leaguering for the night made tactical sense.

The Scots, being outnumbered, would probably have used the cover of darkness to clear off, content with keeping their stolen herds intact. Given how far the beasts had been driven at rapid pace, they probably needed to rest before going on to make that long climb to the border, so hanging on at Otterburn and bashing away at the tower didn’t appear to entail much risk, as the speed of Hotspur’s reaction was partly unanticipated.

Even if March and Douglas were in part surprised to find themselves under attack, their dispositions were still sound. The livestock was guarded by defences in a lower camp close to the river garrisoned by light troops and camp followers who could give a decent account of themselves, holding out long enough to be reinforced. Meanwhile, the Scots main camp holding the bulk of fighting men was further up the hill and to the north, out of sight of anyone approaching from the east. March clearly trained his men at arms in a flanking manoeuvre executed if attacked frontally, using a shallow but well-screened re-entrant to mask their deployment. Walking the ground today confirms the feasibility of this and we know the scrub and tree cover was denser at the time.

The battlefield

Hotspur was relying on speed and dash rather than careful reconnaissance, and he’d be aware of the risk that entailed. His plan to divide his forces makes sense if we accept that he knew the location of the Scots lower camp but not of their main fighting base. What developed were almost two separate battles. Percy’s subordinate brigade commanders Matthew Redmayne and Richard Ogle performed their task admirably and beat up the Scots guarding the camp and their hastily dispatched reinforcements.

Fatally, however, the flank attack developed into a wild pursuit and they were unable to come to Hotspur’s aid. As Percy hesitated, as would be necessary to marshal his men for the second prong of his assault, March gained the respite he needed.

If, as I’ve suggested, Hotspur commanded up to 7,000 mounted men, his column in line of march would have stretched back for up to 8 miles and taken a deal of time and sweat to deploy. It may be that a large part of his strength never in fact engaged, and I think that at this point the number of soldiers directly under Hotspur’s command and those now led on their flanking march by Douglas were probably about equal.

As the English force came north from Elsdon, they’d know the enemy was close, as would the Scots. Much has been said of the Scots being surprised, but both sides would have had their prickers ranging. The English must surely have noticed the absence of livestock, the Scots having lifted all they could and whatever the locals had failed to spirit away or conceal. As we know when foot and mouth disease emptied the fields in 2001, a rural landscape suddenly cleared of livestock is uncannily disquietening.

At what point did the fighters dismount? I think Hotspur dismounted his men as he prepared to deploy, and this would take time. I don’t believe Douglas (who would lead the Scots flank attack) would have been mounted, as Scots tradition was to fight on foot in dense packed spear phalanxes (the schiltron). That short distance over difficult ground implies the Scots came on foot, marshalled into battalions so they could deliver their own counter-attack while maintaining surprise, and with it, tactical initiative.

Initially, the English were caught off guard, but they soon rallied and were able to hold their ground. The fight degenerated into a grinding stalemate in which the English possibly still had an advantage in numbers, though would be worn down by their exhausting march, while Douglas’ men were fit and rested.

Both sides had reason to feel confident in their officers, and if the Earl of Douglas had been reading up on Robert the Bruce, he’d do what the great man did at Bannockburn (1314) and keep a battalion in reserve to deal a decisive blow. I’m as sure as I can be that is what he did – his attack was a sound and well-executed strike against Percy’s extreme right flank.

The earl led from the front and it cost him his life, but his men did not spot his fall, so they did not lose heart. Their tactic was a well-rehearsed manoeuvre and Douglas’s charge the signal for renewed effort along the line, renowned paladins like Sir John Swinton literally hacking a path through the English line.

Harry Hotspur’s statue at Alnwick Castle

We can study plans of troop deployments and movements on maps, but we must bear in mind that while careful cartography appears to make sense of events, it is never like that on the day. Medieval commanders had no means of controlling a fight once it began other than by flags or messenger. “No plan ever survives contact with the enemy” is a sound military maxim and the face of battle changes everything.

Finally, after much hard fighting, Percy’s line faltered and broke, knots of fighters spilling untidily in the gathering dusk. If we assume the English reached the battlefield at around 6pm and were attacking on their left by 6.30pm, with Douglas’ counter punch ramming home at around 7pm-7.30pm, that’s over an hour of decent daylight to win the day. I don’t believe the battle was at any salient point fought by moonlight, but the pursuit, if there was one, would have been.

On the English left, Redmayne and Ogle pelted after their beaten opponents, losing all contact with Hotspur on their right and playing no further significant role in the overall decision. They cheered after the fleeing Scots, relieving them of anything worth retrieving.

On Hotspur’s right I’m going to offer the heroic assumption there was no rout, and that while many men were captured, a large part of Percy’s tail would have got off in good order and retreated towards Elsdon, harried all the way but still in fighting trim.

How do we explain the interment of many, presumably English, dead in a mass grave at Elsdon when at the time bodies were habitually buried close to where they fell rather than being carted off for burial elsewhere? I suggest this was the result of a negotiated truce. These were not uncommon, and while I cannot begin to prove it, it is a tantalising possibility. After the battle, the Scots remained in possession of the field, but I think they may have agreed to allow the English to remove their dead. We don’t know who the dead of Elsdon are, though it has been widely posited they must be casualties of the battle. We won’t know until further forensic archaeological work is undertaken.

What does the Battle of Otterburn tell us about Hotspur as a commander? He lost and is invariably described as rash and impetuous. His decision to attack at dusk or at least evening is routinely cited as folly, but this isn’t necessarily so. Having tracked the Scots and regained for the first time in that campaign a measure of tactical initiative, he had no choice but to press this advantage or see it vanish. Attacking at vespers would hand him more than two hours of daylight, and medieval battles rarely lasted that long.

The monument to the battle

He had never led a sizeable field force into battle. Medieval commanders didn’t like battles, they were too unpredictable, impossible to control, and failure meant catastrophe. Percy had made his formidable reputation as a leader of light cavalry, ‘hobiler’ warfare perfected by both sides on the Border Marches. Success, as he’d demonstrated, demanded dash and vigour, and he had plenty of both. It took nerve, which he had, fine judgement, and some luck. Trying to translate hobiler tactics onto a larger battlefield was tricky; different dynamics applied as command and control was far more difficult.

A key element in conventional combat was, as ever, intelligence gleaned through reconnaissance. This was lacking – a serious flaw – so he would be attacking while not knowing, (a) exactly where his main enemy was stationed, and (b) the clear potential of dead ground which Douglas had previously spotted. We could say the Scots won because their close appreciation of ground was superior.

Another serious failing on Percy’s part was his inability to coordinate the two pincers of his assault. Redmayne and Ogle did well at the outset, achieving their key tactical objectives, but seemingly had no orders or possibly couldn’t control their men when it came to reforming. Whatever the reason, he lost perhaps a third or more of his force who, had they been able to support his wing, might well have tilted what was a fine balance. What we can say is that Hotspur gambled, took a significant risk and lost. History tends to be hard on losers. Yet his contemporaries didn’t seem to blame him.

John Sadler has had a lifelong interest in military history. He now combines writing with lecturing in History at Newcastle University and working as a battlefield tour guide, living history interpreter, and heritage consultant. He is a keen re-enactor and a long time member of the Sealed Knot Society. He is the author of more than 40 books and lives in mid-Northumberland. His latest book, Crucible of Conflict: Three Centuries of Border War, is published by Whittles Publishing, priced £18.99 in softback.