Well read

David Dobbin (on the ladder), and Ian Varty with some marbled papers

First published in edition 196 of The Northumbrian, Oct/Nov 2023

Dedicated bibliophile JANE PIKETT goes behind the scenes at Newcastle’s Literary & Philosophical Society to learn about the ancient craft of bookbinding from the people keeping it alive

In an almost impossibly exciting development for a wet Thursday afternoon, I find myself escorted into the bowels of the Literary & Philosophical Society of Newcastle – most historic and esteemed seat of research, learning and letters, and arguably the finest private library in the country.

Here, I am shown into a small room, a little larger than your average secondary school store cupboard, which, I am told with some reverence, is The Bindery (no capital letters grammatically necessary, but for me the importance of what goes on here makes them essential).

This place of historic presses, papers and book cloth; brass type, needles and threads; brushes and tapes, rulers, stamps, glues and finishing tools, has little changed over decades. Every shelf and cabinet is covered in tools, equipment, and books awaiting repair or rebinding – each sent down by the librarians upstairs, who slip little notes inside with a list of recommendations and requirements. “They seem to appear sometimes overnight, says volunteer bookbinder Miriam Haddad, as if they are delivered by the library elves.”

A shelf high above head height is home to old sewing frames which have held goodness knows how many books and been used by goodness knows how many hands. A guillotine awaits its next victim, pasting brushes soak in cleaning solution, a rounding and backing press stands ready to bring new life to a well-read tome.

Miriam Haddard in the bindery

Miriam is one of the volunteers who help to restore the Lit & Phil’s collection. Her name is scrawled on a label on the front of a little drawer in a wall-length cabinet holding the volunteers’ tools. She opens hers to reveal a box of treasures including tissue paper, a box of papers and ribbon, headbands (the decorative ribbons which often top and tail the pages at the spine of a hardback book), vintage linen thread, various tools, threads and more.

She’s been bookbinding for 14 years, on the recommendation of an occupational therapist. “As occupational therapy goes, I don’t think you can do much better,” she says. “It is absorbing, calming, and you end up with something you’ve restored or made. It is very gratifying.”

This magical place is a rarity, explains Paul Smith, longstanding member of The Society of Bookbinders North East. “We think this is the only independent library in the UK with a bindery. Bookbinders elsewhere are always amazed to hear there is not only a bindery here, but opportunities to gather here three times every week to bind books.”

One of these sessions is in progress in a large room next door to the bindery. Having been told the library’s volunteer bookbinders are at work, I assume I am to meet three or four dedicated souls probably as old as the library toiling away in a dusty Dickensian basement. Instead, I discover a large room in which I count 17 or 18 folk of varying ages, conversation buzzing as they each get on with their own job in hand, supervised by a kindly young dreadlocked professional bookbinder named Tim.

Volunteer Gabi Recknagel allows me to look on as she brushes glue onto the spine – naked for the first time since it was bound decades ago – of an old book secured in a wooden press. Over this she presses a strip of mull (a strong open weave cloth) to strengthen it and then pastes over it again, ready for the addition of a cardboard spine.

“Tim the bookbinder tells us what to do and then I fumble my way forward and hope for the best!” she says, adding that she only started volunteering in January and is learning as she goes along with the support of Tim and her co-volunteers.

I have three guides in tow. There is veteran binder Paul Smith (mentioned above), Ian Varty, bookbinder and maker of sublime marbled papers used as end papers, and David Dobbin, who has invited me to see this work going on in advance of The Society of Bookbinders North East exhibition early next year.

He didn’t have to work hard to get me here. Firstly, I have a passion for books. Not only the written word, but also as pieces of art in their own right – their paper, layouts, fonts, cover designs and everything else a source of fascination and at times adoration. Plus, at the heart of the exhibition will be my Northumbrian colleague Charlie Bennett’s book, Down the Rabbit Hole, which I edited and published for him. For the exhibition, Charlie has donated a number of unbound copies of his book, 12-15 of which will each be bound by members of the society and put in show.

Paul Smith has bound one copy, which now has pride of place in Charlie’s study (“It’s so beautiful I almost blubbed when he gave it to me,” says Charlie, with characteristic openness), while the hardback edition (p21) carries an exquisite marbled endpaper design by Ian Varty.

In addition to this weekly Thursday session for Lit & Phil volunteers, several of whom are also members of The Society of Bookbinders North East along with David, Paul and Ian, there are two other weekly sessions where people can learn to restore their own books.

Paul was one of two founder members of the Lit & Phil group in 1997. Others joined rapidly and since then they have bound in excess of 5,000 books. For decades Paul has also been active in The Society of Bookbinders North East, which holds regular meetings and occasional exhibitions showcasing the work of members.

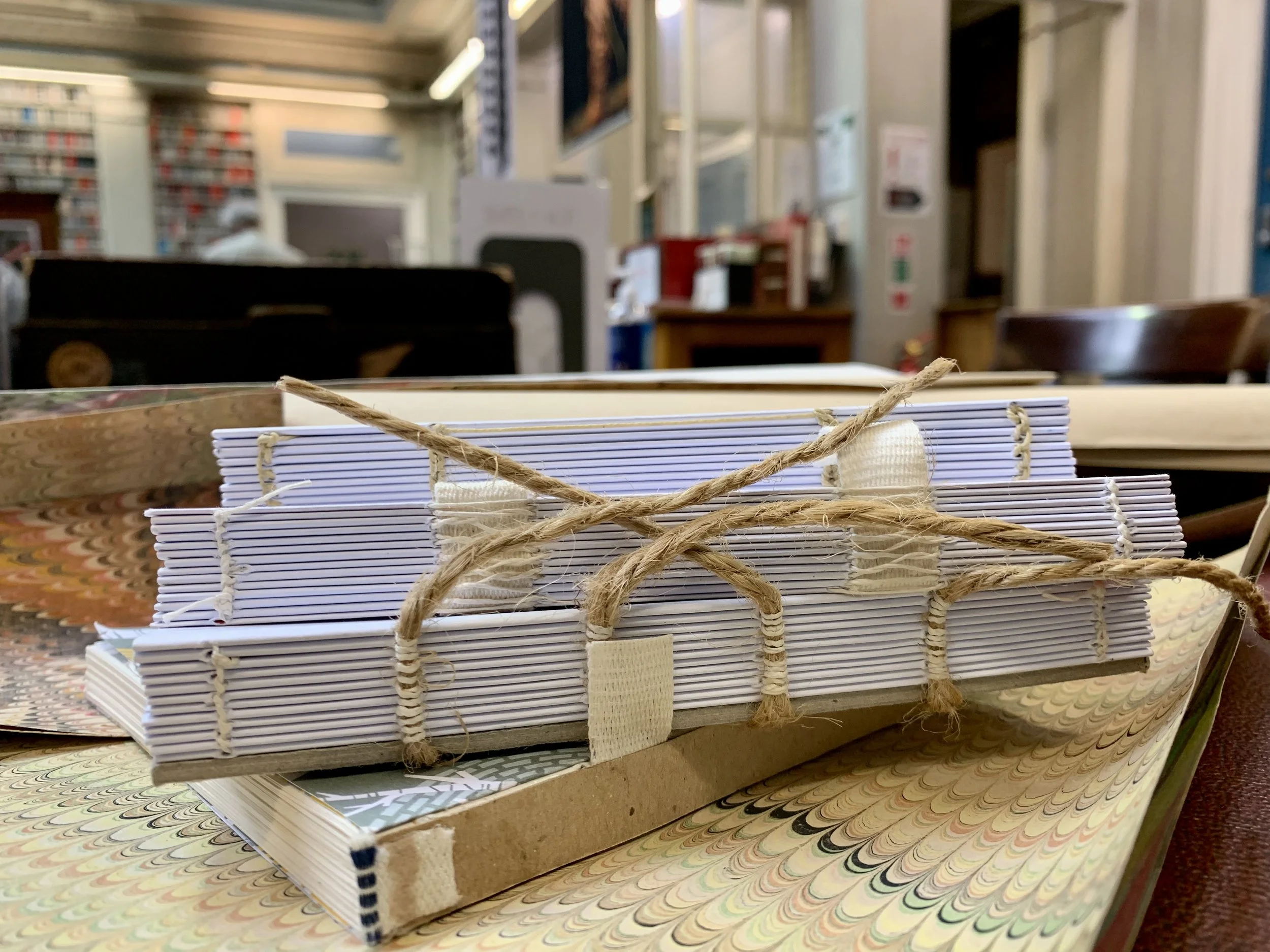

Some of David Dobbin’s bound books and paper inners, with marbled papers by Ian Varty

An inventive lot, David recalls books bound with boards made from the Lit & Phil’s old floorboards, books bound in old maps, and another covered in leather in the design of a miniature briefcase complete with tiny metal buckles and a lock.

David has brought along a bag containing volumes he has bound according to various methods and materials (a multitude have developed over the centuries) plus some inner page sections stitched to various methods to show me the different techniques and materials in play. When you are restoring a book, you start by ‘pulling’ it – literally pulling it, carefully, clean of its backing, says David: “You then reveal the inner pages, which are made up of groups of folded pages called sections and sewn together. You take out all the glue, tape and thread and just start again.”

It all sounds extremely satisfying – the bibliophile’s version of stripping down a car engine, cleaning it up, restoring and rebuilding it. Whether you’re restoring or binding a new book, you then sew the sections together. Depending on the technique being used, you might incorporate tapes or cords running across the spine to affix the front and back boards to the text block, and use different stitches, such as a type of cross stitch which creates ‘chains’ which secure the pages to the covers, which would traditionally be covered in leather or vellum, book cloth or paper.

“The modern book,” says David, “whether it is paperback or hardback, is essentially a creature of machine production. But in Samuel Pepys’ day, for example, he would take the text block of a book to his bookbinder who would bind it to his directions. Today he would be hard pressed to find a hand bookbinder, but there remain enthusiasts who keep the art and craft alive.”

Stitched page sections

As David says, the book as a concept may be well more than 5,000 years old, though its format has changed over time. The codex, the paged book we are familiar with today, has been with us for some 2,000 years.

David, a former lawyer, took up bookbinding as a hobby when he retired 12 years ago. Meanwhile, Ian, a retired plasterer, started binding around 2016 and then progressed into paper making and marbling, learning by trial and error and a lot of help from the internet.

He works at home in a bedroom, his worktop two pieces of ¾” plywood topped with blotting paper resting on a clothes airer. To create his exquisite marbled papers he manipulates paint on a solution created when he boils an Irish seaweed called carrageen moss in water.

You might think a bookbinder requires a shed full of specialist tools, but David says there are many kitchen table binders doing a good job armed with basic craft tools and knowledge gleaned from workshops such as those at the Lit & Phil.

Whatever each binder’s level of experience or expertise, every person I meet today is dedicated to, and indeed somewhat evangelical about, their craft. Paul Smith, a retired NHS clinical psychologist, is among the most experienced here. His journey into bookbinding began when he started collecting antiquarian books. “Many of the books I bought were in poor condition, so I took up bookbinding to restore them. Once you get into it, it adds another dimension to the world of books,” says Paul, who started binding back in 1980.

He can’t say definitively how many volumes he has bound over the years, but estimates some 4,000 in his collection were bound in his home bindery. His preferred techniques range from the half leather and board 19th Century technique, which he began with, to many older styles, including unusual ones. “Bookbinding brings together many interests. I particularly enjoy taking an old and interesting book in poor condition and either re-binding it or restoring it and then reading it.

“But you can look at binding from many points of view. Many people regard a book as an art object, but when you take it to pieces, or pull it, to its original, that’s archaeology. In recent days I have been working on a 17th Century book. You’re aware that when you’ve taken the spine off you’re the first person to see that since the original binder.”

The materials used in old books paint a social history, he adds, such as book cloths made from slave-produced cotton, which prompts pause for thought. They are also works of art – every hand-bound volume a one-off. There is a display cabinet in the Lit & Phil displaying the work of the bookbinders, which includes a copy of Paul’s daughter Jessica Irena Smith’s novel The Summer She Vanished, recently published in softback by Headline, alongside a one-off copy bound in 19th Century-style leather and marbled boards with marbled endpapers by proud dad Paul.

Whether restoring or hand-binding a new volume, this is time-consuming, painstaking, and absorbing work. “Hours and hours go into each book,” David says, “not just in doing the work but in terms of thinking time, often in the bath. And it’s worth every minute of it.”

Volunteer bookbinders’ drawers and equipment in the Lit & Phil bindery