Strike derailed

The wreckage after the derailment

ROB SCOTT chronicles a notorious event during the 1926 General Strike, which saw the imprisonment of eight Cramlington miners for the derailing of a passenger train and is now the focus of a new play

As we rapidly approach the centenary of Britain’s only general strike, it is timely to recall one of the most notorious incidents of May 1926, when a group of 40 striking miners inadvertently derailed The Flying Scotsman, which was carrying 281 people, at Cramlington in Northumberland.

The event is now largely forgotten, but it is the focus of a new play, The Cramlington Train Wreckers, by Northumbrian-born playwright Ed Waugh. He explains: “It was May 10, seven days into the nine-day General Strike. The intention was to take up a rail then wave down and stop a black-leg coal train, but the gang inadvertently derailed a passenger train carrying 281 people. Mass deaths were only averted because the volunteer driver had been warned of trouble ahead and slowed down, the crash resulting in only one minor injury.”

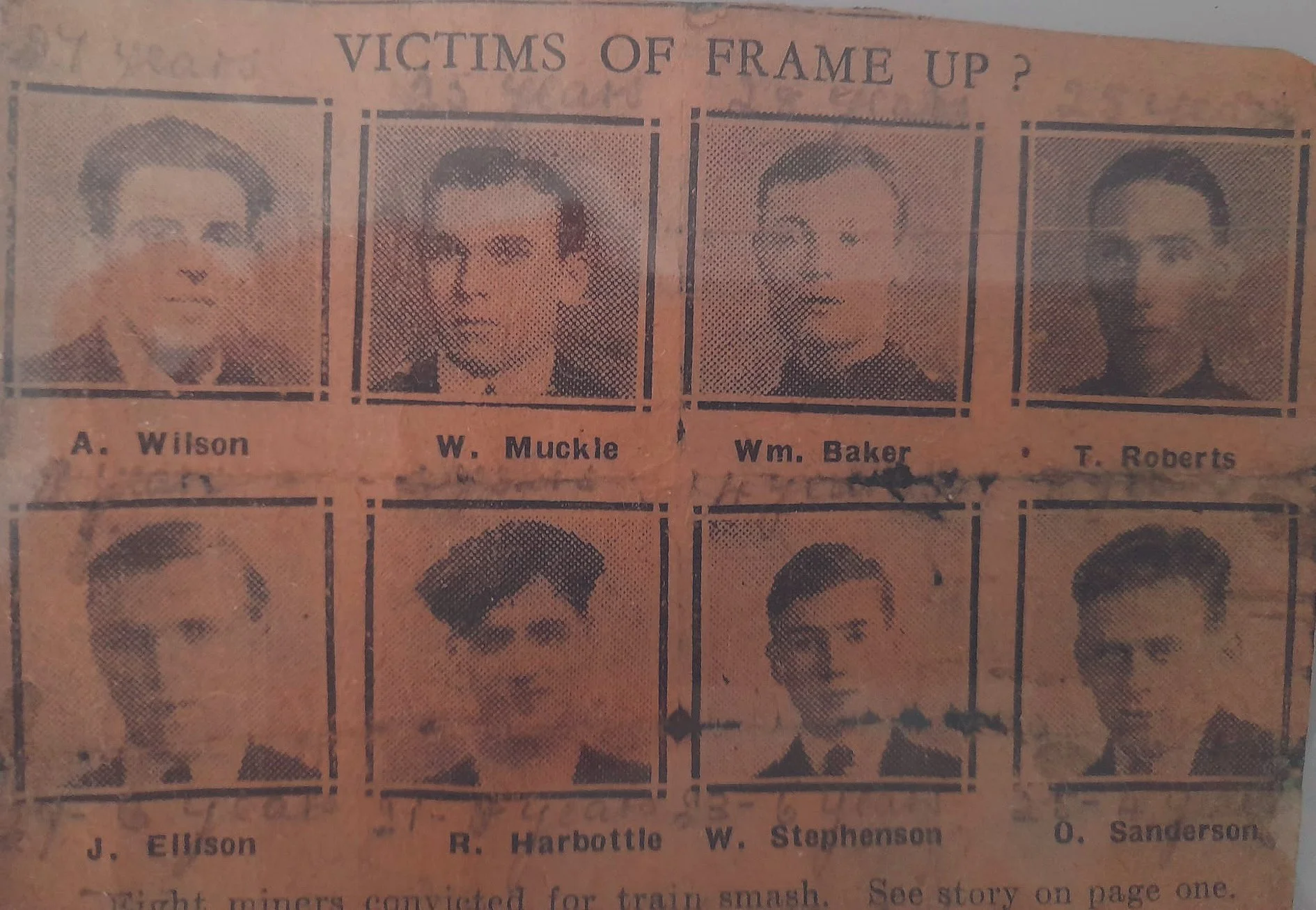

Eight Cramlington miners were sentenced to a combined 48 years for their involvement in an event that made national and international headlines and was raised in parliament by irate Tory MPs and Lord Grey of Fallodon. However, like most of the subjects covered by playwright Ed, this has been lost in the foggy realms of history – until now.

Ed hopes the play will refresh local memories. “I’d always intended to write a play about the General Strike,” he says. “Then I read about the Cramlington train wreckers in Margaret Hutcherson’s excellent book, Let No Wheels Turn: The Wrecking of the Flying Scotsman, and I was stunned to discover that a man who turned King’s Evidence in court against his fellow miners and friends was called Lyle Waugh. My maternal grandmother was from Dudley mining stock. Was I related to Lyle Waugh? Research revealed I was not, but my interest in the subject was piqued.”

Back to Monday, May 10, 1926, and at Cramlington Miners’ Institute there was a mass meeting. Here, union official Bill Golightly (the actor Robson Green’s grandfather) called on members to “stop everything on wheels”. A group of some 40 miners went out and took up a rail on the East Coast mainline, intending to wave down and stop the black-leg train. They had not intended to derail it, but that was the result, and eight of the Cramlington Train Wreckers, as they became known, ended up in prison for their trouble.

Questions were raised in the press about the prison sentences

William Baker, 28, Oliver Sanderson, 25, and Bill Muckle 25, were sentenced to four years; William Stephenson, 22, and James Ellison, 29, each received a six-year sentence; while Robert Harbottle, 21, Thomas Roberts, 25, and Arthur Wilson, 26, each got eight years.

The Cramlington Train Wreckers is seen through the eyes of gang member Bill Muckle. In his 1981 autobiography, No Regrets, Bill wrote of the conditions of the mines at the time: “We were treated like slaves. The pits were wet with foul air...there were no pithead baths... there was no yearly or statutory holiday pay. We lived in cramped houses and the toilets were earth closets... water was drawn from a standpipe 30ft from the house. When the pit bosses demanded a 40% reduction in pay in 1926, the balloon went up and we came out on strike.”

Ed, whose well-known plays include Carrying David about boxer Glen McCrory, and Wor Bella, about heroic World War I women footballers, explains: “The General Strike was the biggest rupture in society since the English Civil War of the 1640s. Today, we can’t fully understand how polarised Britain was during the nine days of the strike. Little moved and the Establishment feared an extension of the Russian revolution of 1917.

“Soldiers coming home from the Great War had been promised ‘a land fit for heroes’, but that hadn’t materialised. There were mutinies in the British army from the end of 1918 and even the police went on strike in 1919. The mines, which had been nationalised during the war with huge payments to their owners were returned to these owners in 1921 and they demanded the miners, who had saved the war effort, take a 40% wage cut.”

In late 1924, Conservative Stanley Baldwin was elected prime minister with a 209 seat majority. Seven months later he declared that all workers must take a wage cut. This was, Baldwin said, “in the national interest” to get the economy on a sound footing.

The battle lines were drawn. Mine owner Lord Londonderry said: “We must smash the trade unions from top to bottom,” while Winston Churchill, chancellor of the exchequer at the time, described the situation as a class war.Thus, at a minute to midnight on May 3, 1926, a general strike was called by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) and the country came to a standstill. When the TUC called off the strike nine days later, there was huge opposition from its own members. Indeed, the miners stayed out for a further five months, causing terrible poverty and resulting in the likes of Hurst Park in Ashington being turned into a tent city after striking miners and their families were removed from their company homes.

“More than 10,000 strikers were arrested during the nine days of the General Strike, some just for picketing,” says Ed. “There is strong evidence that the Cramlington miners were used by the Government and judiciary as an example against working class resistance.”

The train wreckers were eventually released from prison early due to pressure from union members, politicians and the judiciary itself. When Bill Muckle, William Baker and Oliver Sanderson were released on September 1, 1928 after serving two years, three months, they were greeted as heroes at Newcastle Central Station. “According to a police spy, there were 3,000 people on platform 6 to greet them,” saya Ed. “A brass band played The Red Flag and thousands applauded on the streets as they marched up to Haymarket for a rally.”

Trying to downplay the martyrdom of the remaining wreckers, the authorities made the other early releases more secretive, and on Thursday, July 11, 1929, William Stephenson and James Ellison were freed after serving three years. Five months later, Arthur Wilson, Tommy Roberts and Bob Harbottle were released (after three and a half years) on December 23, 1929.

The Cramlington Train Wreckers, which is supported by Arts Council England, will tour the North East in November. Venues include Alnwick Playhouse, Queen’s Hall in Hexham, and Cramlington Learning Village Theatre. For further details visit: www.cramlingtonterainwreckers.co.uk