Shepherds to the rescue

A Wellington bomber

MICHAEL LYONS recalls the saga of Wellington Z1078, one of the WWII aircraft to crash in the Cheviots requiring rescue from local shepherds

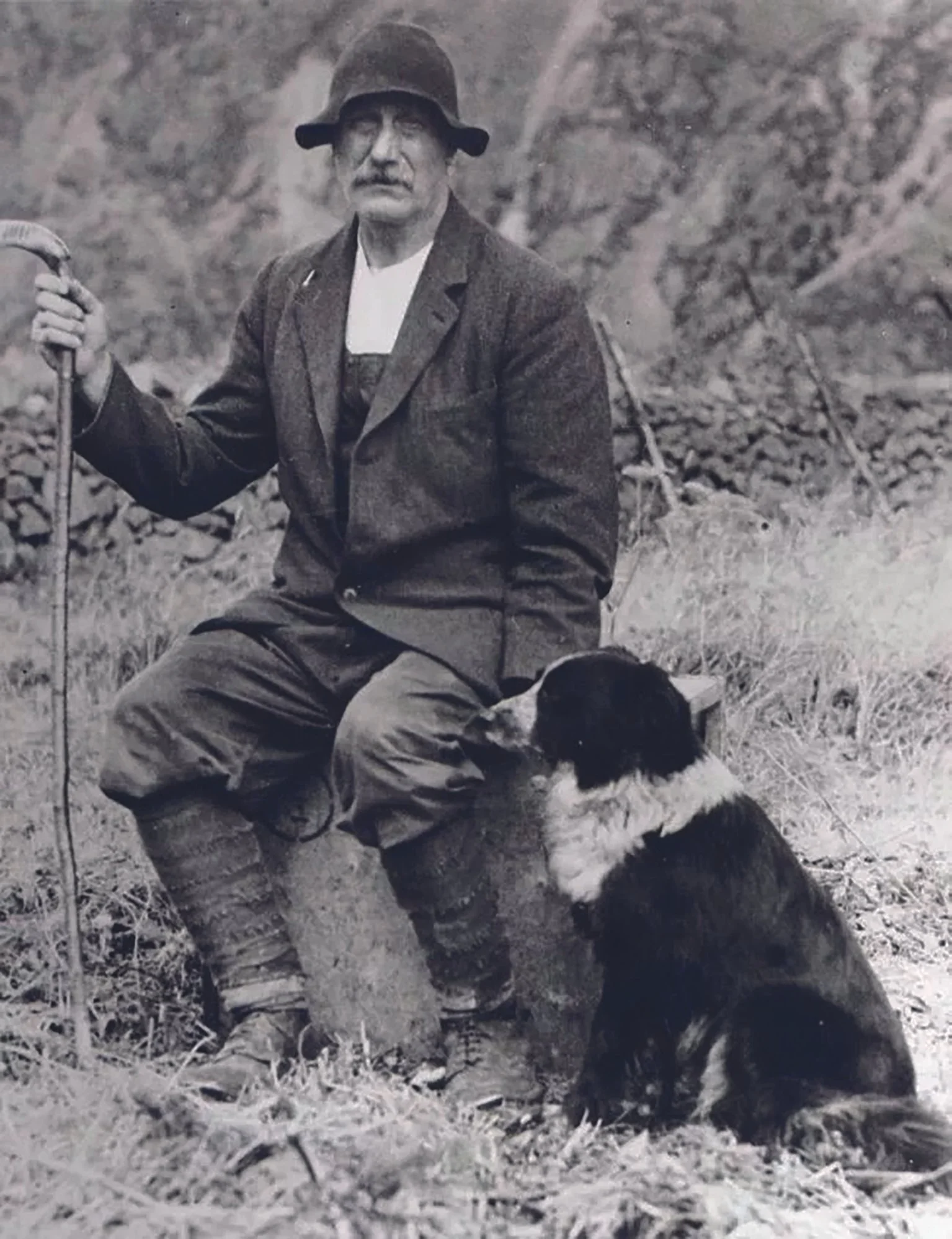

The photograph of shepherd John Dagg with his collie dog Sheila which appeared alongside Helen Brunton’s poem about their involvement in the rescue of four allied airmen following a crash in the Cheviots in December 1944 (The Northumbrian, issue 199), prompted me to recall another dramatic episode on the flank of The Cheviot nearly two years prior.

My research into the crash landing of Z1078, an RAF Wellington bomber (aircraft known affectionately as ‘Wimpeys’), has revealed fascinating insights into the lives of College Valley shepherds at the time. I was fortunate to co-interview Dagg’s son, also named John and now aged 91, who was present, aged nine, when the following events took place and which his sister Margaret included in her 2005 book, A Child of the Cheviots.

The Dagg family had moved from their home at Rookland in Upper Coquetdale to Dunsdale, a steading in the College Valley, in May 1939, three months before the outbreak of World War II. Few farmhouses in England are more remote than this. Today it is available to rent, a beautifully appointed holiday home in rugged country, but life here for the family was hard. Lying in the shadow of The Cheviot and a crowd of its lesser brethren, it abuts Bizzle Burn, which when charged with snow hurtles down from Bizzle Crags on the shoulder of Northumberland’s highest hill.

From Dunsdale it is 5½ miles down to Westnewton and, at the time of the crash, anything resembling a decent road. A further 6 miles distant, Wooler is the nearest settlement of any size. To get anywhere, a bike or Shanks’s pony were the family’s usual alternatives to John Dagg’s workhorse, which he was loath to use for trips. A bus service calling at Westnewton was a welcome lifeline.

Shepherd John Dagg and his dog. Sheila

At the time, sheep were the lifeblood of the valley and more than a score of hired shepherds worked there. The landowner paid John £2 10s a week and he had to pay an assistant shepherd out of this, so John, his wife Margaret and their four children had to be self-sufficient. In addition to his pay, John’s ‘pack’ (his total package), included two milking cows and several sheep. The family kept hens, had an extensive vegetable patch, and wild rabbit was often on the dinner menu.

Our story begins in Wooler just before midnight on January 15, 1942. The winter of 1941/42 was one of the worst John Dagg had seen; he even reported icicles on his moustache. On this night, Archie Guthrie, one of Dagg’s shepherd neighbours from nearby Southernknowe, was on his way home from a dance in Wooler. Having become something of a strategic linchpin against the prospect of enemy incursion from the North Sea, the population of the village and its hinterland was considerably swollen by hundreds of service personnel. The dance venue, Archbold Hall, and cinema, the Drill Hall, were welcome diversions.

As he made his way up the valley against the snowstorm, Archie heard aircraft engines and realised a plane was too low over the hills. Minutes later he heard a crash and saw flames near West Hill Cairn on the flank of The Cheviot. Despite by now having trekked over 10 miles from Wooler, he hurried to find fellow shepherd Jimmy Goodfellow from Southernknowe and together they climbed some 1,000ft up towards the crash site. As they ascended, they encountered a lone airman struggling down in stockinged feet. This was rear-gunner Sergeant Cyril Glover who had been forced to abandon his flying boots when his legs become entangled in the Wimpey’s damaged rear gun turret. The shepherds helped him down to Dunsdale where they roused John Dagg and his daughter Margaret from their beds.

Earlier that night, at around 5.30pm, Z1078 had been one of 14 Wellingtons that took off from RAF Snaith in East Yorkshire on bombing sorties to Hamburg. Only 13 returned, their crews reporting that anti-aircraft flak had been moderately accurate but not intense, and no-one had seen Z1078 hit. What they didn’t know was that the aircraft had become separated from the other bombers and its navigation aids had failed. As it reached the British coastline, the weather worsened and visibility was dire, offering the navigator little to assist him in pinpointing their location. In fact, the Wellington had strayed too far north over the North Sea and was on a direct course for The Cheviots.

On board were six airmen, including Pilot Officer Bert McDonald, a Canadian; two New Zealanders, sergeants Larry Hunt and Tom Irving; and three RAF sergeants, Fred Maple, Bill Allworth and Cyril Glover. Too late, the pilot realised the imminent danger and the Wellington ploughed into West Hill. Fortunately, it avoided nearby crags and the peat layers where the plane came to rest may have absorbed some of the shock of the crash, but Hunt and Maple were killed and Tom Irving was seriously injured.

McDonald, Allworth and Glover suffered non-life-threatening injuries, but stranded in a blizzard in inhospitable territory, they were less than hopeful of rescue. Only Cyril Glover was fit enough to go looking for help, and he had no boots, so he was fortunate to come across the two shepherds who brought him to Dunsdale, the nearest house. With her mother away visiting family, young Margaret Dagg tended to the airman, who begged John Dagg to help the other survivors freezing up on West Hill.

The indefatigable Archie Guthrie now made for Hethpool, 4 miles back down the valley, where there was a telephone. At Southernknowe he paused to send another shepherd, Jimmy Douglas, to help Dagg and, leading Dagg’s horse, the two set off up the hillside, following the western edge of the Bizzle Ravine towards the summit of West Hill. There was no let-up to the snow and the horse slipped and slid up the icy track as they followed the stench of the Wimpey’s burning wing to the wreck’s location.

At last they were able to make out the plane’s carcass framed in the snow and, finding the remaining survivors, they now faced an even more dangerous prospect – a treacherous descent with one very badly injured airman, two with various wounds, and all three suffering from severe exposure.

Following Archie Guthrie’s phone call, and with nearby RAF Millfield yet to be commissioned, medics and a salvage team were dispatched from RAF Acklington, nearly 40 miles away. Sadly, the medics were too late to save Sergeant Irving. The three others, McDonald, Allworth and Glover, were whisked back to RAF Snaith the following morning, where, according to Margaret Dagg’s account, “We were told they had been made to fly the next day so as not to lose their nerve.” Tough times indeed.

The task now was to dismantle Z1078 and recover serviceable parts before burning the rest. Once again, the shepherds were asked to act as guides for the RAF salvage team. A squad of the Kings Own Scottish Borderers was also dispatched from nearby Doddington to guard the wreckage. Much to John Dagg’s amusement, their role was to prevent German spies or fifth columnists stealing the aircraft’s guns or sensitive parts. He doubted if any such infiltrators would dare to go up West Hill at night in such weather. The soldiers even proposed pitching a tent near the wreckage, but changed their minds when Dagg assured them it would soon be blown clear over the top of The Cheviot.

The three dead crewmates were laid to rest with full military honours in the cemetery at nearby Chevington on Monday January 19, 1942. Sadly, Sergeant Cyril Glover was the only member of the crew of Z1078 to survive the war; both Bert McDonald (August 1942) and Bill Allworth (October 1942) died in subsequent air accidents. John Dagg, Archie Guthrie and their fellow shepherds continued to save the lives of airmen on The Cheviots, the most celebrated instance being that of the American B17 that crashed nearly two years later on December 16, 1944. Their efforts, as well as those of the aircrews, are commemorated by a memorial erected at Cuddystone in 2018.