Northumbrian Greats: Thomas Cobden-Sanderson

Thomas Cobden-Sanderson, looking every bit the Bohemian, photographed in August 1902 (source: Bonhams)

In the latest in his series celebrating great Northumbrians through history, Stephen Roberts profiles the famed bookbinder, pioneer in typography and friend of the Arts and Crafts movement, Thomas Cobden-Sanderson (1840-1922)

A Northumberland-born printer, book designer and binder, Thomas Cobden-Sanderson (1840-1922) would become a leader of the 19th century revival in artistic typography, though he also famously made quite a splash by chucking the type which became his signature in the River Thames, more of which later.

Born in Alnwick on December 2, 1840, Thomas James Sanderson was son to James Sanderson, a district surveyor of taxes, which sounds as popular an undertaking as an estate agent or traffic warden. Thomas was in his teens around the time the 4th Duke of Northumberland was employing architect Anthony Salvin to make significant modifications to Alnwick Castle’s interior. Thomas’s mother was Mary (née Rutherford How); the elder of his parents by some 13 years. He attended a number of schools before entering Owen’s College (Manchester University) and then Trinity College, Cambridge to study law. He left without taking a degree, but still entered Lincoln’s Inn as a barrister.

In 1882 Sanderson married Julia Sarah Anne Cobden (known as Anne), at which point they both took on the surname Cobden-Sanderson in an early adoption of the double-barrelled nomenclature that seems to have become popular these days, though sadly not all today’s constructs roll off the tongue as elegantly as theirs. Anne was a socialist, suffragette and early vegetarian. From a wealthy family, her father was Richard Cobden (1804-65), the Radical and Liberal politician, co-founder of the Anti-Corn Law League, and free trade campaigner.

Cobden-Sanderson became a member of the Hammersmith Socialist League and worked with William Morris, doyen of the Arts and Crafts Movement which stood for traditional craftsmanship and was anti-industrial in its philosophy. It was during a dinner party with Mr and Mrs Morris that Cobden-Sanderson was persuaded to get involved in bookbinding, which he took up in 1883 and in which he would quickly achieve distinction.

Anne was also supportive of a move into bookbinding as she was concerned that her husband’s interests were too ‘abstract’, (i.e. airy fairy), and that it was vital he began ‘doing’ rather than just thinking if they were ever to get any money behind them. Thus, Cobden-Sanderson founded a workshop in 1884, bidding farewell to his law practice at the same time.

Morris and Cobden-Sanderson shared the belief that the art of bookmaking was being destroyed by mass production, and the bindery was dedicated to producing high-quality books with great attention to detail and design. It was the main bindery used by Morris’s Kelmscott Press for a period of time, and the closure of Kelmscott saw Cobden-Sanderson set up his own press, of which more later.

In 1887 he suggested the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society was a suitable name for a new group, and in the process he seems to have christened the influential movement. The Doves Bindery, meanwhile, was duly established in 1893 in Hammersmith, London, after which Cobden-Sanderson restricted his work activities to designing. The name came from a nearby pub, The Dove, a boozer with literary clout as it was frequented by the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Graham Greene, and Dylan Thomas. Cobden-Sanderson’s friend William Morris lived handily right next door, and James Thompson is also said to have written the words to Rule Britannia! there. It remains a popular spot, its riverside terrace packed with punters on summer days.

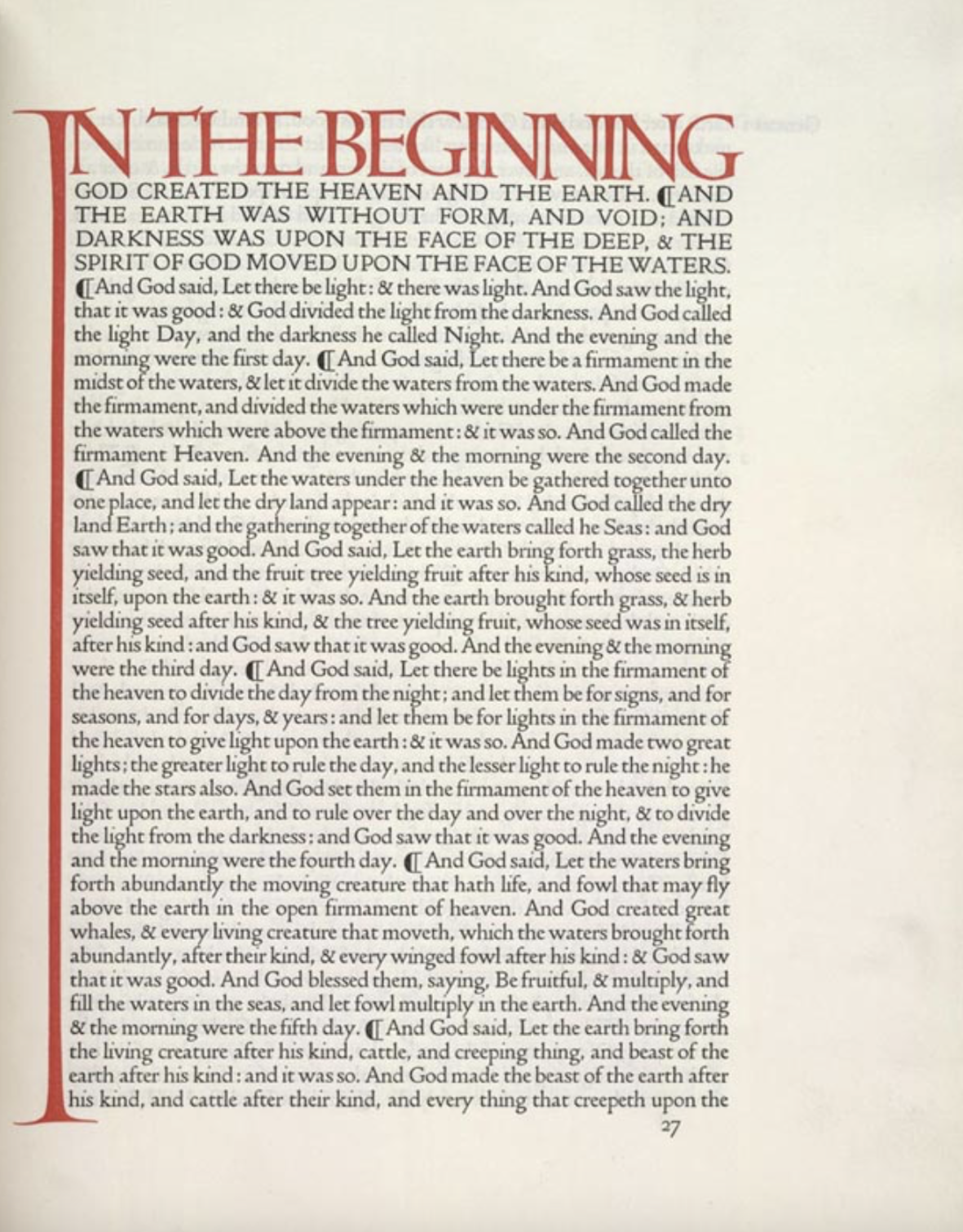

Given what’s already been said, we should perhaps not be surprised that it was the more practical Anne who effectively ran the business while her husband did whatever it was that the creative mind did, including probably imbibing at The Dove. In 1900, Cobden-Sanderson launched the Doves Press which published the famed Doves Bible (1903), which ran to five volumes and was Doves Press’ undoubted magnum opus; the ‘restrained splendour’ of the company’s output described on several occasions as ‘unsurpassed.’

Cobden-Sanderson (right) with his business partner, Emery Walker

Emery Walker (1851-1933), the London-born engraver, printer and photographer, came in as a partner at the outset and was another leading figure of the Arts and Crafts Movement, as well as being instrumental in overseeing the introduction of Doves Type, which was based on a Roman typeface by Nicolas Jenson (1420-80), the French engraver, printer and designer, and was used in all Doves Press publications.

Cobden-Sanderson had some American female pupils who took his bookmaking ideals back across the pond, where his name also became known. Unfortunately, Anne was imprisoned in 1906 for her suffragette activities, which made her husband’s trip to the US for a lecture tour the following year quite eventful as they had to enter America from Canada because any attempt to sail to the States directly was likely to result in problems with immigration given Anne’s notoriety. Anne delivered at least one talk on the subject of women’s rights there though, while Cobden-Sanderson was quite adept at slipping his own thoughts on the suffrage into his lectures.

Not everything was rosy in the world of Doves Type, however, and come 1909 there was a bitter and long-running dispute in progress between Cobden-Sanderson and Walker concerning the rights to the type and the pending dissolution of their partnership. It was eventually agreed that those rights would settle on Walker, but only after Cobden-Sanderson was pushing up the daisies. The press eventually closed in 1916 and Cobden-Sanderson did what any disgruntled businessman would have done in such circumstances – he chucked the type, punches and matrices into the River Thames, which in the pre-digital age appeared to be very much the end of the precious typeface. (It is not known if PC Plod asked questions about this rather odd case of aqua fly-tipping, but if he had, we like to imagine he may have asked: “And were you aware, sir, that the Thames is for trout and not type?”).

This was certainly one way of trying to ensure no-one else could use the precious typeface, and Walker was furious. However, Cobden-Sanderson had died by 1922 when Walker decided to pursue legal action, so he sued Anne Cobden-Sanderson and was awarded £700 in damages, which was a significant sum at the time but far less than the potential value of the type itself.

While all this was going on, Cobden-Sanderson maintained a number of influential and articulate friends, including the politician and writer John Russell, Viscount Amberley (1842-76), son of the two-time Whig and Liberal Prime Minister Lord John Russell and father of the philosopher Bertrand Russell to whom Cobden-Sanderson became godfather. When Bertrand was convicted in 1918 for lecturing against the USA’s entry into World War I, it was Cobden-Sanderson who spoke out in his defence. Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), the painter, was another friend. Cobden-Sanderson published his Journals, 1879-1922 in 1926 and Cobden-Sanderson and the Doves Press: The History of the Press and the Story of its Types by AW Pollard (1929) offers further depth if you can get hold of it.

Doves Typeface meanwhile, thought to have been lost forever, has been digitally recreated in recent years and 150 pieces of the original type have been recovered from the bottom of the Thames close to Hammersmith Bridge. Thomas Cobden-Sanderson died on September 7, 1922 at his home, 15 Upper Mall, Hammersmith, a house that bears an English Heritage blue plaque. He was 81. He hadn’t quite managed to take all his secrets, or his typeface, to the grave.