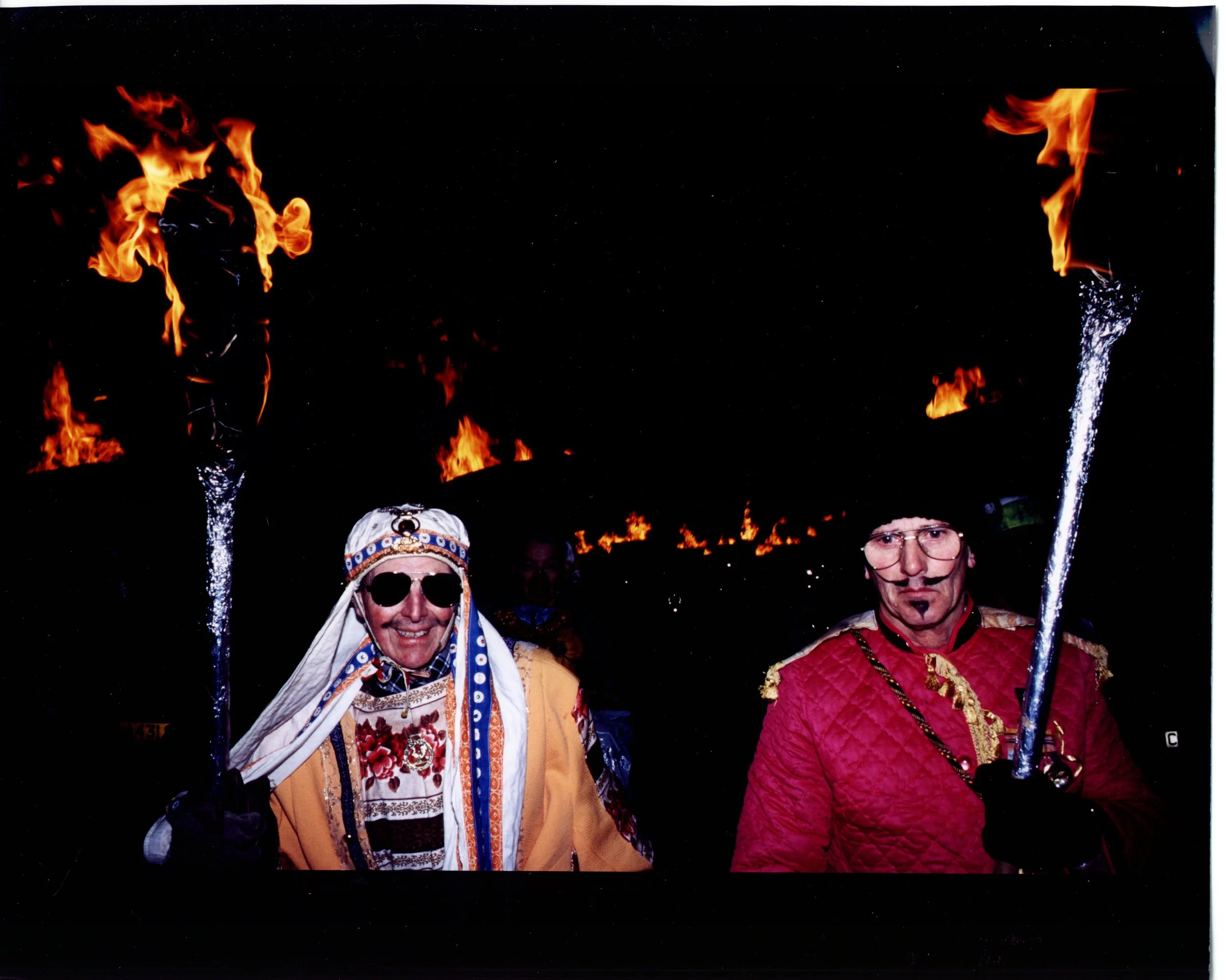

Nowt so strange as folk

Allendale’s New Year Tar Bar’l procession c.1970, with at the centre Joseph Bell (1908-1982), son of Lancelot Bell, another long-tme guiser who appears in the 1912 photo opposite - an example of the hereditary nature of customs such as these (photo reproduced by the kind permission of Dorothy Collier)

First published in edition 197 of The Northumbrian, Dec/Jan 2023/2024

John Evans chronicles some of the folk customs common to the region, particularly at this time of year

‘Christmas is coming, the goose is getting fat, please put a penny in the poor man’s hat.’ This nursery rhyme was often sung during my childhood in the 1950s, but is heard less these days.

Of course, some Christmas traditions die out over time. For instance, the tradition of guisering – play-acting, or ‘mumming’, by youths – was regretfully reported as having been discontinued in Ford village at Christmas 1903 by the Revd Neville, vicar of the parish, “owing to the lack of young people in the village.”

Thought to be a relic of medieval mystery plays, guisering began a few days before Christmas, when a troupe of youths dressed in outlandish clothes visited local farmhouses. The chief actor in the troupe wore a cocked hat and carried a sword, while his colleagues donned tall hats shaped like archbishops’ mitres decked with ribbons and pictures. Some wore shirts with leather belts and epaulettes of multi-coloured ribbons or paper shreds.

They proceeded to enact a play involving the death of one of their number, ‘King George’, and his revival by a doctor. One of the youths played ‘Betty’, a maid, who ushered in a member of the troupe by brushing the floor with a broom and speaking the lines: ‘Redd sticks, redd sticks/ Here comes in a pack of feels/ A pack of feels behind the door/ Step in King George and clear the way…’

King George then stepped forward with the words: ‘Here I come in myself, sir/ That never came before/ I’ll do the best that I can do/ What can the best do more?’

The next actor, ‘Goliath’, was introduced: ‘He is Goliath bold/ He fought the battle of Quebec/ And won five ton of gold.’ (There was a tradition that a man from Ford was present at the death of General Wolfe in 1759 at the Battle of Quebec during the Seven Years War with France. These lines were probably a reference to this).

There followed a fight in which King George was slain, but Goliath called in a further character, a doctor, who revived him: ‘I am a doctor/ Who can you cure?/ I can cure the hitches, stitches and bitty/ go-hitches.’ (The dictionary defined ‘hitch’ as a ‘temporary stoppage’, and ‘bitty’ as ‘made up of unrelated scraps’, but these words may have lost some of their meaning over the years).

The doctor then revived the king and all said: ‘We will all shake hands/ And will fight no more,’ and the play ended with the guisers giving their host their good wishes and festive greetings before taking a box around to collect money.

The origin of the tradition may be that farm labourers, laid off in winter, did it to raise money. The Revd Neville makes it clear that it had become a custom, rather than a necessity, by the early 1900s and died out because although there were a few lads who intended carrying it on, their courage failed them at the last moment.

Sword dancing was also performed by the guisers in the form of two clowns, a fiddler and a clothes carrier. The leader usually wore a faded uniform and a cocked hat with a feather, while ‘the Bessy’, a clown who collected donations at the end of the performance, wore a woman’s gown and a fur hat with a fox’s tail on it. The other clown, known as ‘Tommy’, may have worn a dress with a fox’s pelt draped over.The troupe would act out a play, reciting rhymes and singing songs before the dancers performed.

William Henderson, in his Folklore of the Northern Counties of England, records: “The five men then commence dancing round, with their swords raised to the centre of the ring, ‘til the first clown orders them to tie the points of their swords in ‘the knot’… The knot is held upright by one of the dancers who they call ‘Alexander’ or ‘Alick’. He then takes his sword from the knot and, retaining it, gives the second dancer his sword. Then the second dancer gives the third dancer his sword… and so on until all the swords are returned.”

I witnessed a similar performance by Morris dancers on Tyneside in the 1980s, and there remains rapper sword dancing – a sword dance using short, flexible blades – which grew from the pit villages of Northumberland and Co Durham.

Some customs have survived and even thrive, such as first footing at New Year. The first footer, so tradition goes, must if possible be someone considered lucky. A woman, a dark man and a flat-footed person are traditionally considered unlucky, and it was considered a most ill-omened thing if the person visiting did not bring something for the table, even if only a piece of bread, a penny, or a lump of coal. It was even unluckier to carry anything out of the house on leaving.

In the past, it was also considered unlucky to light a fire in the hearth on New Year’s Day. This may have derived from the frequent practice, before matches were invented, of neighbours borrowing embers from one another to light candles or fires. A New Year traditionally marks a fresh start and it was thought unlucky to borrow in this way on New Year’s Day.

New Year guisers in fancy dress at Allendale in 1912, Lancelot Bell second left (with thanks to Allen Valleys Local History Group)ndale

To return to guisers, this is the term given to the group of local men who carry whisky barrels filled with burning hot tar (Tar Bar’ls) in procession through Allendale on New Year’s Eve. The men wear colourful fancy dress and have soot-blackened faces. To become a guiser, they must have been born in the Allen Valleys, and many follow their fathers and grandfathers into the tradition. At midnight, they arrive at the Tar Bar’l fire in the town centre, where their test of strength and courage ends in spectacular fashion as they toss their barrels onto the bonfire to welcome in the New Year, shouting, “Be damned to he who throws last!” Then they, along with the band of brass players who follow them, traditionally first foot around the village.

Allendale 1990

Another custom that survives in some areas is the rolling of eggs on Easter Monday. Common in Europe in the early last century, children were presented by their elders, friends and tradesmen with eggs which they boiled and decorated with paint. The children then assembled in a field with a steep slope and bowled the eggs uphill with as much force as they could. The object of the game was to find out whose egg would hold out the longest without breaking, or to find out who could throw their egg furthest. According to the Revd Neville’s account: “In the old days, whin [gorse] blooms were used to dye the eggs with the pointed end of a rushlight [or rush candle]. The resulting grease preserved the pattern while the egg was being dyed and was afterwards rubbed off, leaving the decoration.” (A Corner in the North: Yesterday and Today with Border Folk, Hastings M Neville, 1909).

In Norham-on-Tweed during Lent, children played with a ball, striking it on the ground. Each time it rebounded they would say: ‘Tid, Mid, Misersay/ Carlin, Palm and Pace-egg Day...’ This was their way of counting the Sundays in Lent as they looked forward to Easter. Many adults today may remember painted boiled eggs from their childhood, and have heard the rhyme above being recited.

Meanwhile, the Rev’d Neville recorded another tradition: “The fifth Sunday in Lent is remembered by some of the old folks and is called in the Church Pasion Sunday. It was the custom to eat fried peas on this day. The custom was kept up in Norham-on-Tweed at the time of writing [1909]. The carlings were peas steeped in water, and then fried in a yettling [a pan] with brown sugar and rum or whisky, sometimes brandy. The village inn was the scene of much feasting on the carlings, which were prepared and served gratuitously to all customers who came.”

It must be remembered that the usual food of the people of the time had little variety, so fried peas were regarded as a delicacy. This charming custom can thus be seen for its practical value.