Northumbrian Greats: The Brothers Dalziel

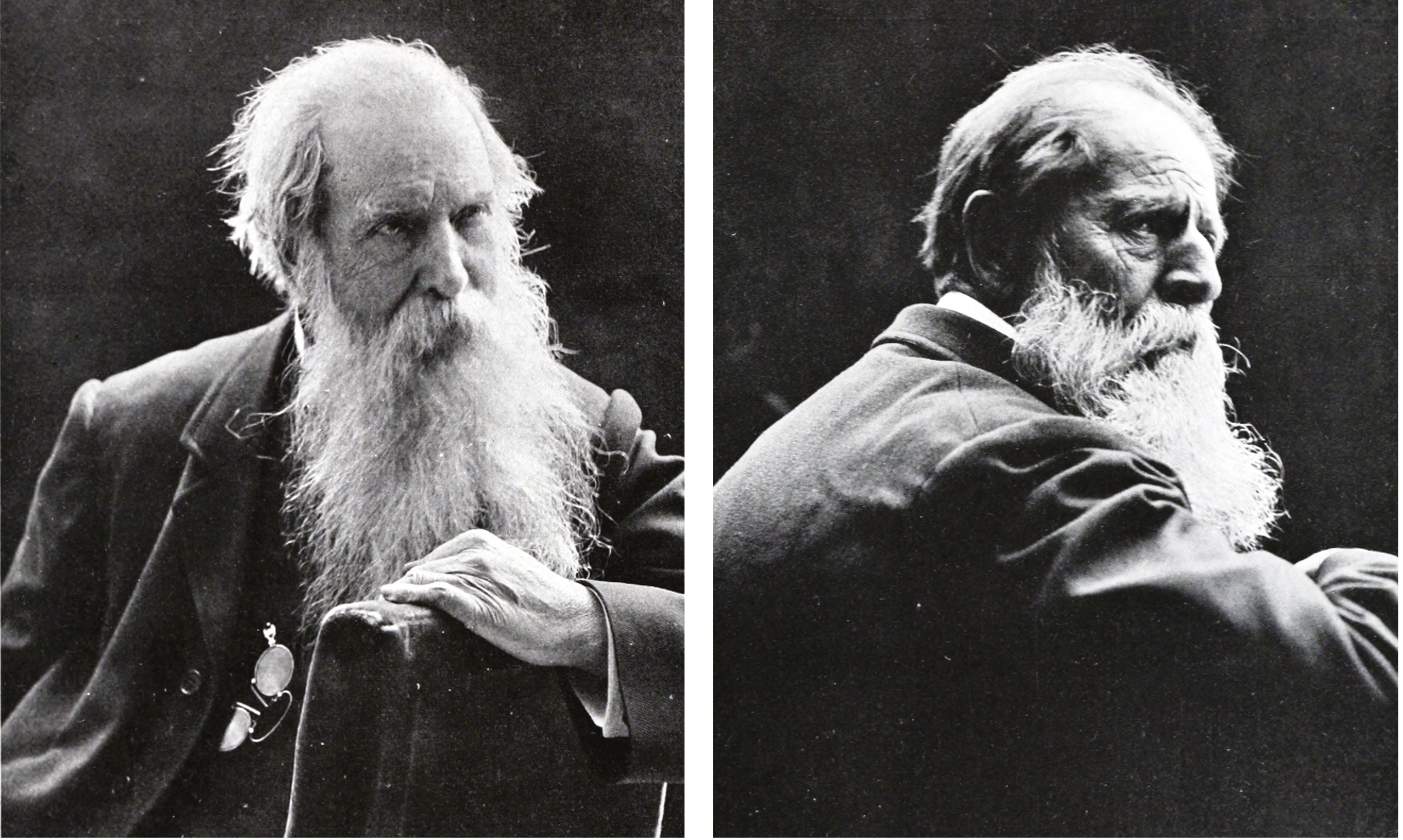

George (left) and Edward Dalziel

First published in edition 197 of The Northumbrian, Dec/Jan 2023/2024

In the latest in his series profiling notable Northumbrians through history, Stephen Roberts chronicles the lives of the brothers (and indeed sister) Dalziel behind the famed Victorian wood engraving business which made their name famous

There were the Brothers Grimm, purveyors of fairy tales, the Brothers Karamazov conjured up by Fyodor Dostoevsky, and our own Brothers Dalziel (pronounced ‘Dee-ell’) – prolific and inventive wood engravers, draughtsmen, printers, publishers and entrepreneurs.

In 1839 George Dalziel (1815-1902) established what was to become a flourishing London-based engraving business. He had trained in London under the watchful eye of Charles Gray, an eminent wood engraver, from around 1835, having travelled from Northumberland to the capital via sailing ship. His choice of profession led to Dalziel (and later his siblings) being known as a ‘pecker’ or ‘woodpecker’; the London colloquialism for those earning a living from wood engraving (I think we all see what they did there).

George’s brother Edward Dalziel (1817-1905), the fifth of the 12 sons born in Wooler to the Northumbrian artist Alexander Dalziel, would also become a wood engraver, arguably the family’s finest, joining his brother George in London around the time the business was established in 1839 or shortly thereafter.Certainly, he had joined George in the business by 1840, and they ran it together for more than half a century. It was a good time to be in the trade, as engraving was the mass medium of the time; the preferred and practical method for illustrating books, magazines, catalogues, newspapers, even packaging. The Dalziels made their money in making the engraved wooden blocks from which the illustrations could be printed en masse.

Ubiquitous at the time, the Victorian equivalent I suppose of today’s mobile phone photo, the only drawback of engraving was that it was labour intensive (unlike today’s Instagram immediacy). Of all the London engraving concerns at the time, it was The Brothers Dalziel who became the most substantial, benefiting from the many plus points inherent in wood engraving (i.e, it was cheaper than copper or steel engraving, capable of incredibly fine detail, and enabled relatively inexpensive mass production).

The brothers gradually built up their business empire, having been joined by a third brother, Thomas (1823-1906). A sister, Margaret (1819-94) and another brother, John (1822-69) would also play a part, these additional siblings joining the family firm during the 1850s, though George, Edward and Thomas always remained at the core of the firm.

Margaret was a talented senior engraver, but the firm remained The Brothers Dalziel, in line with the time’s social norms. Of all of the siblings, though, it seems that Edward was the truly gifted engraver. The youngest, Thomas, or to give him his full and rather impressive nomenclature, Thomas Bolton Gilchrist Septimus Dalziel, was well known, being responsible for illustrating some of Charles Dickens’ work, Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, and The Arabian Nights. Having said that, at least one expert has labelled his output ‘workmanlike’, so I stick with my assertion that Edward was the familial star, George perhaps its business acumen.

Working with several accomplished artists, the brothers would produce a mass of illustrations for the magazine and book business that was very much on the up at the time thanks to increasing rates of literacy, a burgeoning middle class, printing improvements and cheaper book production costs, all of which boosted the market.

‘The Mad Pranks of Robin Goodfellow (Puck)’ by John Franklin, engraving by Edward Dalziel from Gammer Gurton’s ‘Pleasant Stories of Patient Grissel’, 1845 (source: State Library of New South Wales)

Some of the better-known of these artists were William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, all the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and the American artist James McNeill Whistler. The Dalziels were lauded for their fine engravings of Millais’ illustrations, and for illustrating famous works including the Alice books of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense, and some of Tennyson’s poems. They established Camden Press in 1857 (to 1905) which enabled them to commission and print their own works. Not everything they produced was as exciting as Alice, Tennyson etc, however, as they also produced medical journals and even diagrams for plumbers.

In addition to illustrating the work of other authors, the Dalziels produced their own independent works including religious material with artwork by Millais. They also adopted a lucrative side-line contributing humorous cartoons to magazines including Fun, which they eventually bought in 1865. They also made use of the illustrator, cartoonist, and humourist John Tenniel (1820-1914).

Although the business employed many non-family members, all the engravings were signed Dalziel, so it is impossible to know who the craftsperson was in most instances. Most literature included pictures by this time and by the 1860s the art of illustration was in its golden age, the name appearing alongside the illustrations in many books published over 50 years being Dalziel. Indeed, the work of the brothers was much in demand until the introduction of photo-mechanical processing around 1880. This development would see book and magazine illustrations take on a whole new look, and eventually put the Dalziels out of business in 1893. But while their work may have been superseded, it is not lost. There are examples on display in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, for example, while the British Museum has a Dalziel Archive of well over 50,000 proofs – testament to how prolific they were. They certainly cornered the market while they could.

At the end of the 19th Century, sensing their time was up, they collaborated on an autobiographical account of their work entitled The Brothers Dalziel, A Record of Work 1840-1890. During their heyday, they influenced how the readers of books, newspapers and periodicals viewed the world. After all, most people couldn’t take or see photographs, so if the brothers said an ostrich resembled a zebra, then it probably did.

The west side of Highgate Cemetery is home to many Dalziels, with family vaults belonging to both George and Edward, and a grave for Thomas. Sadly, there are few surviving images of the Dalziels themselves, their work proving to be more durable than the photographs that helped to put them out of business.

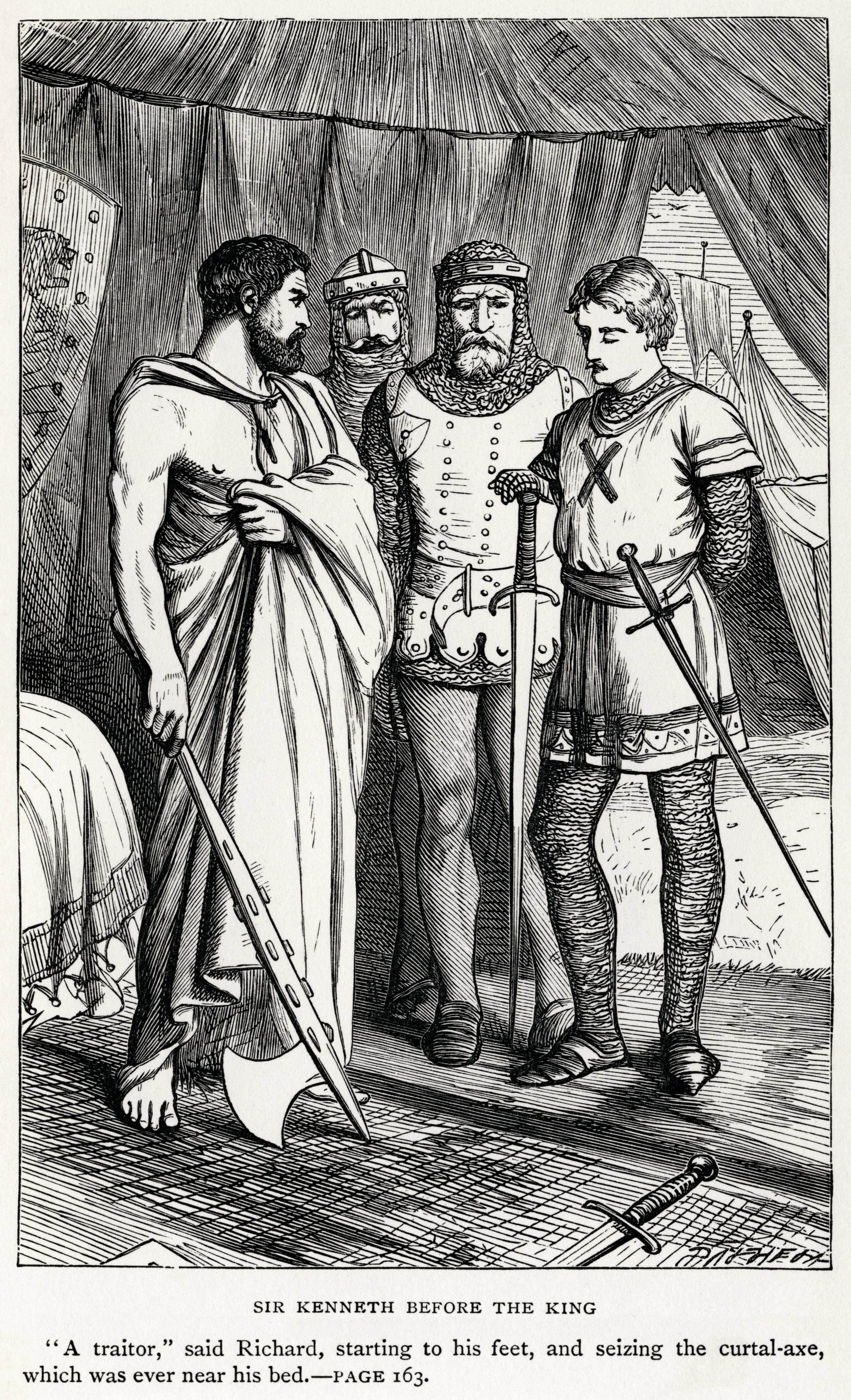

Sir Kenneth Before the King featuring King Richard I, the Lionheart, left (from The Talisman and the Chronicles of the Canongate by Sir Walter Scott, vol. XX of the Waverley novels, 1887)

CHRONOLOGY

c.1835 George Dalziel begins training as an engraver in

London under Charles Gray.

1839 The establishment of the Dalziel engraving business,

with George its prime mover.

1857 The Dalziels establish the Camden Press to

disseminate their works.

1865 The firm purchases the magazine Fun; a vehicle for

its cartoons.

1893 The end of the Dalziel business as photo-mechanical

processing takes over.

1902 Death of the founder of The Brothers Dalziel,

George Dalziel.