In loving memory

The family sculpture on the green by the church

JOHN GRUNDY sets out to look at the history of Ponteland, only to be distracted by St Mary’s church, whose memorials offer a poignant insight into local family history

A question about Ponteland – is it a village or a town? The internet can’t make up its mind. One site plumps for town, the next settles on village. It doesn’t look very big when you’re driving through it and it has always been a village in my mind, but it has a larger population than Alnwick.

It’s also unusual (and I imagine pretty annoying) that a fairly major road goes right through the middle of it, but despite the traffic it has a nice feel. There are a couple of supermarkets (one of them slightly posher than the Grundys tend to use); there are three nice-looking pubs; some restaurants; a sophisticated-looking wine bar; and a caff that has always appealed to cyclists who gather in flocks.

It’s all quite nice, and there’s even a point, as you go across the River Pont and arrive at a roundabout, when you see something unmistakably village-y. Off to the right (if you’re heading north) there is the richly historical church of St Mary the Virgin poised on a village green.

The view of it is framed by trees and includes a surprisingly realistic and attractive large contemporary sculpture of a family group. The green is traversed by a diagonal path which leads on through the churchyard and was used, the afternoon I was there recently, by a stream of schoolchildren on their way home with lots of mums with pushchairs. I sat and watched them, and if I’d needed cheering up it would have done it for me.

The churchyard is a delight. There’s a little water feature burbling prettily with a ring of seats around it and I sat on one of those too and mused about the pleasures to be found in churchyards. This one is rich in trees, including at least one venerable yew, and among the gravestones there are many to attract the eye, including a number of quite richly but quaintly carved 18th century stones.

The church, with the family sculpture on the green

Then there’s the church itself. I’m not going to describe it in detail because it would take too long and bore the bot off most people, but it is a terrific and complicated piece of architecture, 1,000 years of sensitive stitching together and full of beautiful things.

But before I come to those things I have to include a bit of distant background, because once in its history Ponteland hit the national stage. On August 14, 1244 there were probably stories about it on the 6 o’clock news and X (formerly Twitter) because there were English and Scottish armies lined up facing each other across the River Pont.

King Henry III was manager of England and Alexander II led Scotland. They intended to fight a battle about the position of the Anglo-Scottish border, but instead of fighting they signed the Treaty of Newcastle, which established the line of the border which remains today. Plus (as you do – or did in those days) they arranged a marriage between their children; Henry’s six-year-old daughter and Alexander’s five-year-old son. They were actually married six years later when they were 11 and 12, and they went on to have three children (not all at once of course, and not immediately I hope).

Henry’s secretary and chief negotiator on this occasion was Walter de Merton who went on to become Chancellor of England and, possibly as a reward, was granted the rights to the living of the Parish of Ponteland, so he held the rights to all the tithes, i.e. the 10% tax on all the produce of the parish, which was no unsubstantial reward in this fertile landscape. A few years later, he founded a House of Scholars at Oxford. It’s still there and is called Merton College. He gave the Ponteland living to the college, where it formed a major part of its income for the next 600 years, thus inextricably linking Merton College and Ponteland Church.

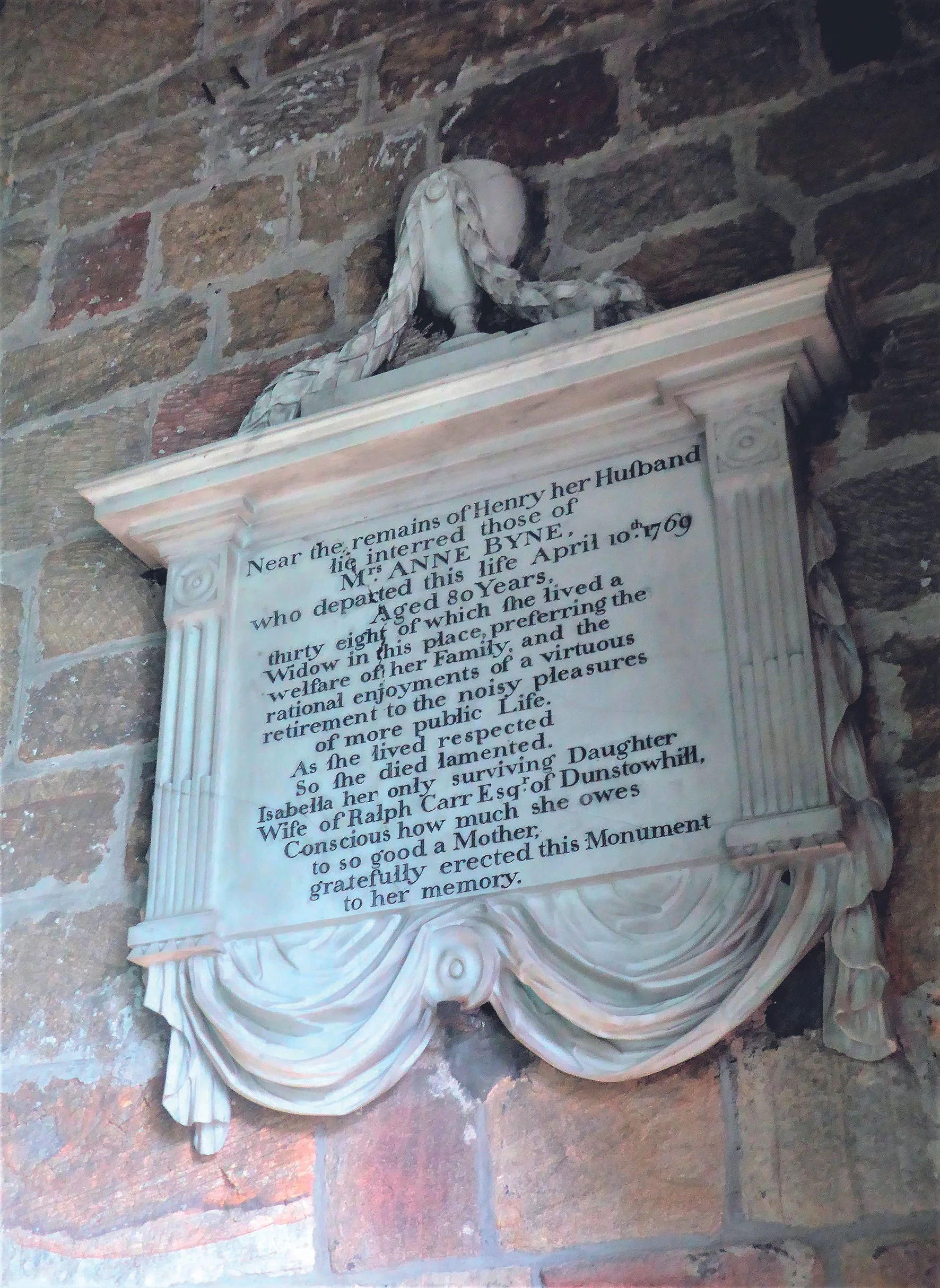

The college appointed or provided the rectors of the parish, and one of them, a man called Henry Byne who had been a fellow of the college, was vicar for a number of years in the first half of the 1700s. He married a lady called Anne and the church contains a memorial with an interesting inscription to her. In fact, the church has two memorials with interesting inscriptions to two women of that name.

Mrs Anne and the Rev’d Henry had three daughters. The eldest was also called Anne, and she was followed by Elizabeth and Isabella. The family lived at Merton House, an elegant early 18th century brick-built rectory which still stands across the road from the church. Sadly, Henry died while his daughters were still quite young, and perhaps even more sadly, two of the girls, Anne and Elizabeth, died shortly after him, leaving only Isabella and her mother behind.

By the time of these events in the mid-1700s, Merton College had stopped collecting the tithes. It was a major exercise and Oxford was a long way from Ponteland so, like tithe owners all over the country, the college leased out the job of doing it to a local agent and shared the profits between them. That agent was a hugely successful businessman called Ralph Carr, from Gateshead, and he not only collected the tithes, but also found himself a wife in the shape of the surviving Byne daughter, Isabella, who provided memorials for her mother and sisters in the church.

I love both the Anne Byne memorials, but I’m going to turn first to the later one which celebrates the memory of her mother, who died in 1769 aged 80:

...38 of which [as the monument reads] she lived a widow in this place,

preferring the Welfare of her family

and the rational enjoyment of

a virtuous Retirement to the noisy

pleasures of more public life. Nowadays, it’s rather fashionable to grow up scandalously and become something raffish like a pole dancer in your old age, but thoroughly respectable Anne sounds grand to me – an example of what my nonconformist aunties would have called “a good living body.”

The second memorial, the one Isabella erected in memory of her sisters, apparently on the advice of her mother, is also about goodness. This is how she describes her sister Anne:

Not more distinguished for the

beauties of her person than those of

her mind.

She naturally applied herself to the

elegant accomplishment of the

polite arts,

In the attainment of which she was so

quick that her knowledge seemed to

be acquired without the time to learn it.

When a child she had the dignity of

a matron.

Though educated in the country

she had the elegance of a court and

an unexampled modesty which never

forsook her, perfected her charms

which were now incapable of addition.

She was adored by her acquaintance

and superior to envy.

Whilst she was approaching the

summit of human perfection Anno

Domini 1741, aged 18, overcome by the

small pox, this lovely virgin yielded to

her fate to rise again in an

inviolable form.

Gosh! And gosh again. She does sound lovely. Sadly (I think it’s sadly. . . perhaps I’m reading too much into it) her other sister seems to get a lukewarm description by comparison to Anne’s:

Near which lies Elizabeth

Not unworthy of such a sister

She died of the same dreadful

disorder in the 16th year of her age.

To the memory of her beloved

sister Isabella

The only survivor of this

raging disease,

by the advice of her lamenting mother

Erected this stone.

I’ve gone on a bit about the Bynes because they’re my personal favourites, but the church is stuffed with things like this – annals of love and family pride, memorials to half a millennium of sickness and sorrow, personal sacrifice and war cover its walls. In fact, war and military matters play a big part in memorials relating to an extraordinary number of different wars. Apart from the 80 men from the parish who are remembered on the 1914-18 memorial, there are others who were involved in conflicts including the Nine Years’ War, the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of Jenkin’s Ear (who remembers that one?), and there’s a beautiful brass tablet engraved in the Arts and Crafts style to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Eustace Guinness, Commander 84th Battalion Royal Field Artillery, who died in the Boer War.

Richard Newton Ogle from nearby Kirkley Hall died in 1795 fighting the French for control of the Caribbean. He was buried at sea and his elegy starts with the magnificent lines:

What though far distant from thy

native land

From friends and kindred far they

poor remains

Now roll beneath the vast

Atlantic surge

Yet still shall live thy memory,

gallant boy

Within our breasts.

There are three other Ogles born at Kirkley over the space of a century, all of whom achieved the status of Admiral of the Fleet. Two of them were called Sir Chaloner Ogle and one of those captured Bartholomew Roberts, the most notorious pirate of the age. All three of these Ogles are to be found on a single monument of family pride put up after the death of the third. Taken all in all, there’s a lot of pride on the walls of St Mary’s Church, and a lot of wealth, too, but that wouldn’t be enough if there wasn’t beauty, profound emotion and loss, and there’s lots of that as well. It’s a lovely place.