“I must own, I wished myself down again . . .”

Wanderer above a Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich (1818)

Was this perhaps how Defoe and his companions imagined the “fearful” summit of The Cheviot? Certainly, they imagined a precipitous point from which any may plunge to their deaths at the slightest gust of wind . . .

Next time you take a winter walk up The Cheviot, spare a thought for the 18th century writer Daniel Defoe who, as MARTIN DUFFERWIEL reports, took his own somewhat alarming stroll up there 300 years ago

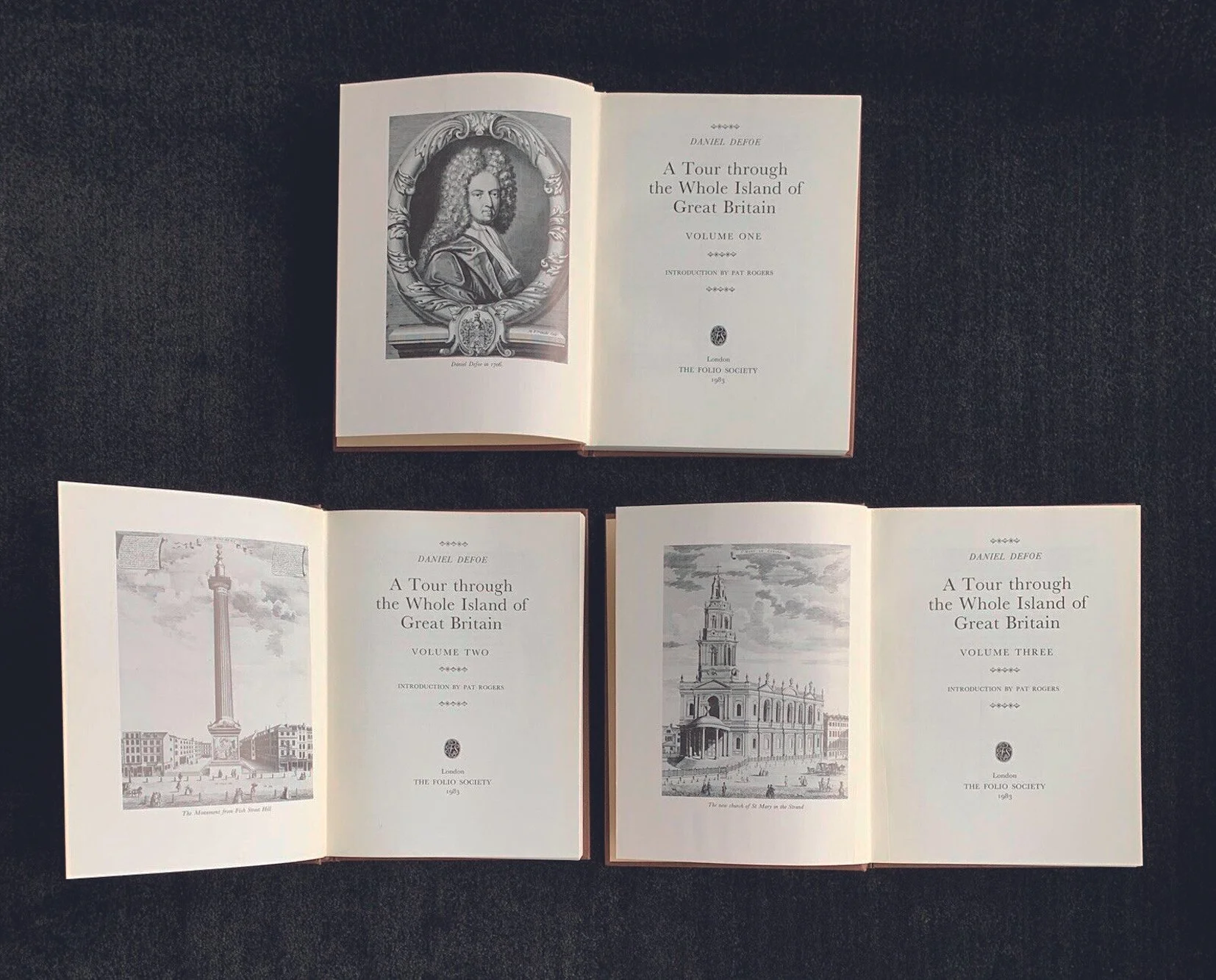

It is 300 years since the first publication of Daniel Defoe’s A Tour thro’ the Whole Islands of Great Britain (published in three volumes 1724-1727), and it was within these popular accounts of his journeys around the country that Defoe regaled his no doubt wonder-struck readership with the singular details of his hair-raising, terror-inducing, death-defying ascent of . . . The Cheviot. An ascent which, according to Defoe, was defined by fear, panic, and the vague, undefined sense of dread of being at the mercy of wild nature in high and liminal realms.

Probably best known as the author of Robinson Crusoe, Defoe had a somewhat eclectic career. Born in London around 1660, the son of tallow chandler and butcher James Foe and his wife Alice, Daniel later added a prefix to his name, it is said because he thought it would make him sound more aristocratic. Among other variations, it was written D’Foe, De Foe, and later the version with which we are familiar today. Occupied variously as a soldier, writer, and pamphleteer, as a result of a controversial pamphlet attacking the High Church, in 1703 Defoe was found guilty of seditious libel, resulting in three days in the pillory before being sent for a short stay in Newgate Prison. Later, he would be employed as government agent, a kind of unofficial spy; and from around 1706 to 1710, he was resident in Gateshead, lodging in Hillgate at the property of a Newcastle bookseller, Joseph Button.

A modern-day eyebrow, possibly even two, might be raised at the level of Defoe’s anxiety during his ascent of The Cheviot; a journey, he tells us, which began in Wooler, “a little town lying, as it were, under a hill,” from where a local guide led him and his party. Explaining first to his readers that the term ‘Cheviot’ was applied not only to “many hills and reachings for many miles” but also to the highest of the peaks, Defoe also claimed to have seen The Cheviot plainly from Roseberry Topping, more than 90 miles away in North Yorkshire.

The author then related that his enthusiastic if inexperienced party began preparations for their adventure. No doubt making a shrewd assessment, their guide suggested that on foot, “it should make a long journey” and assured them he would find horses for their ascent.

Equine assistance duly delivered, the party was appropriately saddled when they were joined by a group of “country boys and young fellows” who had volunteered to accompany the adventurers and “run on ahead”. The party eventually departed, Defoe, his companions, their horses, the guide, and the newly arrived scouts and outrunners comprising a party the size of which, a later writer suggested perhaps a little unkindly, was more conducive to an assault on the Rocky Mountains of the USA than the hills of Northumberland.

Arriving at their destination, their guide led them around the foot of The Cheviot, where Defoe tells of great channels of rocks descending the slopes, “and those, at least some of them, very broad” and indicative, he thought, of mighty winter torrents of water cascading down to crash to the valley floor. He also noted the many alder trees lining the banks of these rocky channels, “so close and thick, that we rode under them, as if in an arbour.”

The party began to ascend, their guide using one of the dry channels to access the higher slopes, but Defoe’s imagination intruded into his thoughts. His party were now, he perceived, like would-be besiegers stealthily approaching a mighty fortification by secret trenches. He was roused from this dream-like state when a new vision awakened a sense of discontent among his party of urbanites, “and we were gotten a great way up, before we were well aware of it.” For the higher they climbed, the narrower the guiding channel became and the comforting shelter of the trees was lost to the widening sky. A new, more discomforting vista was now set out before them. Some of the high surrounding hills, which from the valley floor had seemed to them very lofty, now sat around below them, “low and humble”, yet The Cheviot “seemed still to be but beginning, or as if we were but entering upon it.”

Three volumes of Defoe’s A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain

The terrain now became much steeper, the horses unsettled, and the party slowed. At length, Defoe’s previous dream-like reverie turned into a fearful reality. The height, to them now dizzying, “began to look really frightful,” and Defoe conceded, “I must own, I wished myself down again.”

He reasoned that if their horses should stumble, he and his friends would be thrown and because of the “great steepness of the terrain” would tumble and be dashed against the rocky slopes below. His concerns were shared, it seems, by his companions, who suggested dismounting and continuing on foot. “No! Not yet! But by and by you shall,” came the response from their guide, which under different circumstances and in a different story may have seemed somewhat sinister. So it was that the entourage of boys was at last given serious employment, instructed by the guide to take the horses by the bridles and lead them on. So on they climbed, so high, Defoe states, that their hearts failed them completely. And even though their guide gently mocked them, they could no longer be dissuaded from alighting from their “complaining” steeds.

On foot, progress was laborious and there was talk of going no further as general unease developed into undiluted panic. They began to envision a dreadful scene at the summit, if indeed they ever were to reach it, where they would step out onto some narrow, jagged pinnacle of rock with scarcely room to stand, high above the dizzying chasms below and “with a precipice every way around us.”

Such terrifying thoughts, it seems, collectively overwhelmed the party, and as one they sat on the ground and refused to move another yard, “for all the guides and country boys in Northumberland.” Their bewildered guide enquired as to the cause of their fear. They related their concerns as above, and the previously mocking tone of the guide changed to one of simple and sympathetic explanation of what lay above, where “there was room enough on the top to run a race, if they saw fit,” and neither need they fear being blown off the mountain by the wind.

The running race he suggested was of course never considered, but with his reassurance they carried on and reached the top in about a half hour more. Once there, all previous terrors were put to flight and Defoe describes a smooth and pleasant plain about half a mile in diameter, “which is nowhere even precipitous, much less perilous.” Looking around him, Defoe enquired as to the landscape, discovering that to the east Berwick was visible, and the North Sea, the ‘German Ocean’, “was as if but just at the foot of the hill.”

Our chronicler was fortunate, as on the day he stood atop The Cheviot the views were superb. To the south, 40 miles distant he was told, he could see the salt pans at South Shields, and several notable peaks in England and Scotland were visible. “There was a surprising view of both the United Kingdoms, and we were now far from resenting the pains we had taken,” he wrote. Defoe and his friends began to make light of their previous collective terrors, but were made to feel slightly ashamed on witnessing a clergyman, another gentleman and two ladies on horseback with a guide calmly alighting the summit plain seemingly without a care in the world. “This indeed made us look upon each other with a smile, to think how we were frightened.”

The time had come to depart. The day was clear and calm, just as well perhaps, as Defoe related, still with some anxiety, “otherwise the height we were upon would not have been without its dangers.” The party descended by the same route, the writer pointedly noting that whether on foot or on horseback, the journey down was much more troublesome and tiresome than the journey up. Later, reflecting upon this curious ascent, Defoe wrote: “Thus it is in most things in nature; fear magnifies the object, and represents things frightful at first sight, which are presently made easy when they grow familiar.”