Northumbrian Greats: Sir Daniel Gooch

Sir Daniel Gooch by Thomas Dewell Scott, from The Illustrated London News, 1866

In the latest in his series celebrating great Northumbrians through history, Stephen Roberts profiles that other great railway engineer of our region and some-time collaborator with the Stephensons, Sir Daniel Gooch (1816-89)

They worked hard and died young. This might have been a suitable epitaph for the Victorian railway engineers who literally toiled into an early grave, such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who expired aged just 53.

Brunel’s colleague on the Great Western Railway, Sir Daniel Gooch (1816-89), did rather better, living to the relatively grand age of 73. Gooch was also a famed engineer and Transatlantic cable layer, born in Bedlington on August 24, 1816, just as the railway age was dawning. The son of iron founder John Gooch and his wife Anna Longridge, he inherited a love of mechanics, aged 12 had his own lathe and tools, and was noted as a fearless driver of trucks at the local pit.

In 1831, in Daniel’s mid-teens, the family moved to Tredegar in Wales, where his father John took up a managerial position. This was a stroke of luck for young Daniel as the Tredegar Ironworks became a hotbed of railway innovation. Here, he began engineering training and was fortunate to come across the great Richard Trevithick (1771-1833), who was near the end of his life but still employed by the ironworks to trial an engine there. There was no doubt Gooch recognised the benefit gained from his early exposure to the technology that would transform the country.

Gooch also had early associations with the Stephensons, those other eminent engineers of our part of the world, and collaborated with them. The Stephensons, George (1781-1848) and Robert (1803-1859), don’t need further introduction (though Robert’s dates corroborate my comment about railway engineers’ longevity, or lack of it). Gooch was employed at Robert Stephenson & Co. in Newcastle for a time (1836-37), as a draughtsman. During this period, he met Margaret Tanner, the daughter of a Sunderland shipowner, whom he married in 1838, going on to have six children together. During this period, Gooch also worked on the design of two locomotives, North Star and Morning Star, of which more presently.

But the main thrust of Gooch’s career was with the Great Western Railway (GWR), where he was its first locomotive superintendent from 1837 to 1864, appointed by IK Brunel himself after Gooch wrote asking for a job just prior to his 21st birthday.

One of Gooch’s first contributions was to persuade Brunel to buy North Star and Morning Star from Newcastle, and these formed the basis of the GWR’s early broad-gauge engines, the foundations of its Star Class to which the company would add a further 10 locomotives of its own between 1839 and 1841.

Thus, Gooch played a significant role in getting the GWR up and running with reliable engines. Robert Stephenson is acknowledged as the designer and builder of course, but it is Gooch who was responsible for the acquisition and rollout of these engines into the GWR.

Gooch would quickly see the GWR fleet expanded, designing the new Firefly Class (1840) and in the same year contributing to rail safety by insisting GWR locomotives should always run on the left-hand track other than in exceptional circumstances.

His status is apparent from the fact that Gooch was with Brunel on the footplate when Queen Victoria was treated to her first train journey on June 13, 1842. The loco was one of Gooch’s latest, Phlegethon.

The expansion and improvement of the fleet was aided by Gooch’s development of engines such as the North Briton (1846), while his Lord of the Isles was a gold medal winner at 1851’s Great Exhibition.

The Iron Duke class of locomotives were designed by Gooch. This photograph shows Iron Duke broad gauge steam locos awaiting scrapping after the broad gauge was abolished in 1892 (photo: The Glories of the Railway, 1911)

I’ve mentioned broad-gauge, which was Brunel’s punt on the distance between the two rails (7ft ¼ins). Other railway companies favoured the narrower standard-gauge (4ft 8½ins), which would eventually prevail nationwide, forcing a rare reverse for Brunel. Gooch was active early on in this so-called gauge war, generally designing broad-gauge locos, though he did begin designing standard-gauge classes from 1854.

Although Gooch gave a robust defence of the broad-gauge’s performance, it would ultimately lose out (read on). However, he did put in motion plans for its abandonment and also tried to warn Brunel off his proposed ‘atmospheric railway’ where trains would be sucked along by a vacuum. Gooch was right... Brunel was wrong.

There is a lovely story, probably apocryphal, that Brunel and Gooch were travelling together in a railway carriage as they pondered where the GWR’s principal engineering works should be located.

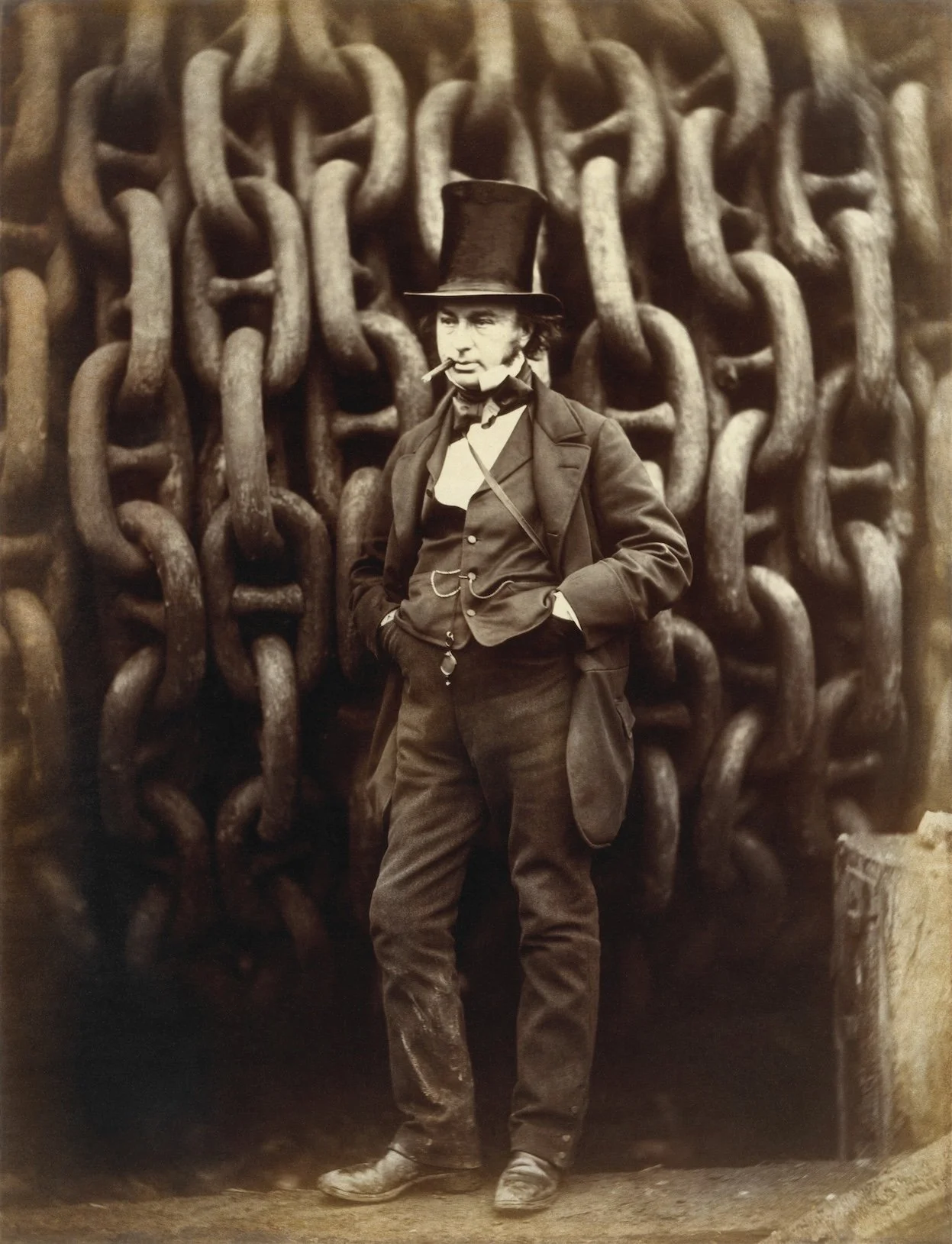

Gooch worked side by side at GWR with the great Isambard Kingdom Brunel (photo: Robert Howlett, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Brunel was said to have lobbed a half-eaten sandwich out of the window, declaring that wherever it landed they would cut the first sod. Apparently, this episode led to the building of the GWR works at Swindon, where the company manufactured and maintained all of its locomotives, carriages and wagons. Thus, on the trajectory of a humble sandwich was determined the location of perhaps the world’s most famous railway works. I like to think this is true, though history tells us that in 1840 Gooch identified the site of the works, so perhaps the sandwich was only as real as a modern train on a strike day.

In 1846 Gooch was responsible for the design of the first complete locomotive built at the works, aptly named Great Western, prototype of the GWR Iron Duke Class of locomotives, which lasted until the end of the GWR broad gauge era. Gooch’s links to Swindon grew strong, and when the town got its first building society (1868), the engineer was appointed its president. In the meantime, he’d also driven the engine on the first return trip between London Paddington and Exeter on May 1, 1844.

In 1847, the Medical Fund Society was set up at Swindon, providing mandatory healthcare for employees and creating a mini-welfare state before the actual welfare state, which was Gooch’s idea.

Given his success and prominence, it was no surprise that Gooch fancied a country pile. He chose Clewer Park in Berkshire, taking up residence in 1859, the year Brunel died. Gooch was distraught at the loss of his ‘oldest and best friend’, but on he went, going on to make another notable contribution, designing the steam engines used when the Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first underground railway, opened in January 1863. He went on to further distinguish himself in submarine telegraphy, laying the first two Transatlantic cables (1865-66) while chairman of the new Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, employing one of Brunel’s steamships, the SS Great Eastern as facilitator. Gooch blew his trumpet in the Foreign Secretary’s direction on July 27, 1866: “Perfect communication established between England and America; God grant it will be a lasting source of benefit to our country.”

Unsurprisingly, given his achievements, he was made a baronet in 1866. He was chairman of the GWR from 1865 until his death and also became an MP in the same year (1865), winning the seat for Cricklade, Wiltshire, which he held until 1885. The fact he was out of the country cable laying at the time of his election was clearly no impediment.

Although he was an MP for 20 years, Gooch never once addressed Parliament, and clearly thought this stoicism was the way to go. “It would be a great advantage to business if there were a greater number who followed my example,” he said. I guess his point was that it’s better to say nowt than nonsense.

Sir Daniel Gooch died at Clewer Park on October 15, 1889 after a lengthy illness. He kept diaries which were edited and published by Sir Theodore Martin (1892), the same year the last of the GWR’s broad-gauge locomotives ran.

Gooch had three brothers who were also railway engineers and the current Great Western Railway company still has a locomotive, 800004, named in honour of him.