Northumbrian Greats: Mark Akenside

Mark Akenside

First published in edition 196 of The Northumbrian, Oct/Nov 2023

Stephen Roberts profiles Mark Akenside (1721-70), poet, physician, disputant, and a name long familiar to the people of Newcastle, even if they don’t necessarily know who he was

A poet of the Enlightenment, moody physician and argumentative disputant, Mark Akenside (1721-70) was something of the 18th Century celebrity, despite his best efforts to rile just about everyone he came into contact with, both as a writer and a medical practitioner.

The second son of Mark Akenside Snr, a successful Newcastle butcher, and his wife Mary (née Lumsden), Akenside was born into a Dissenting family on November 9, 1721, and would be a little lame all his life after an accidental early encounter with his dad’s meat cleaver. Akenside Hill, where he was born and is named after him, was at the time Butcher Bank, so named because of the number of master butchers residing there in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Educated at Newcastle’s Royal Free Grammar School, which was then a Dissenting academy, in 1739 he went to the University of Edinburgh to study theology, soon abandoning this in favour of medicine. Having left Edinburgh in 1741, he returned to Newcastle and began referring to himself as a surgeon, though there is some doubt as to whether he practised at this time.

He did practise in later years, however, but he was of a haughty and pedantic disposition, which hardly endeared him to patients for whom his bedside manner left something to be desired. Indeed, a few years later, the satirical novelist Tobias Smollett appears to have lampooned him in The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle (1751) in the character of the republican doctor.

Akenside could certainly be challenging, if not downright subversive. A gifted orator, he became a sought-after public speaker and fancied a career in Parliament, but, as with those earlier notions of theology, this idea was soon abandoned.

He did, however, take to, and stick to, writing. He began contributing poetry to The Gentleman’s Magazine (a monthly which ran from 1731-1922) in 1737, his first poem being The Virtuoso, and had a small volume of poems published in 1740, including Ode on the Winter Solstice.

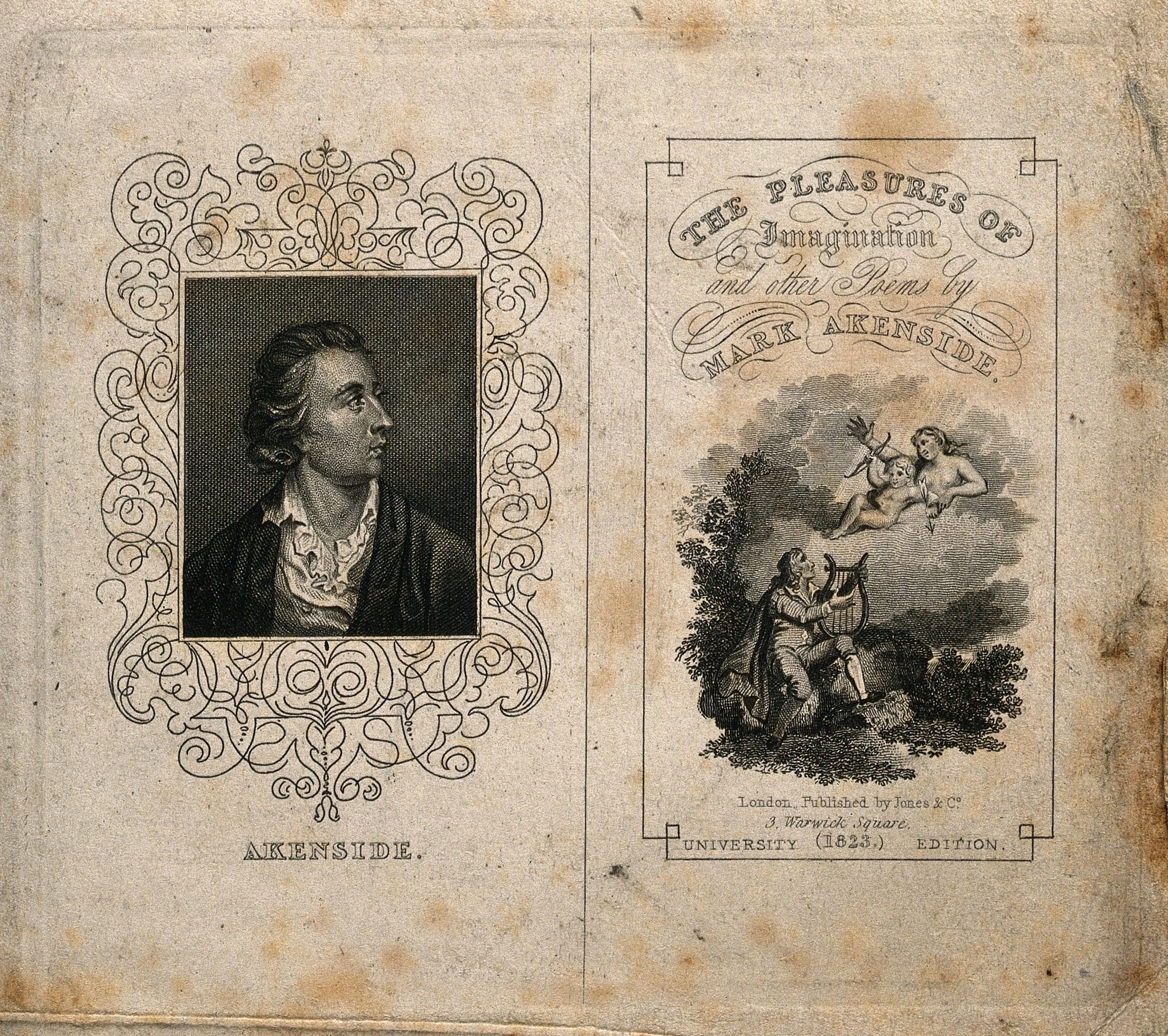

Akenside’s The Pleasures of Imagination, which proved to be his magnum opus

(source: Wellcome Collection)

In 1744, after several years of toil, his magnum opus, the didactic poem The Pleasures of the Imagination, was published. It was apparently on a visit to Morpeth in 1738 that he got the idea for this poem-cum-philosophical essay, which was loosely based on the thoughts of the essayist, poet and playwright Joseph Addison (1672-1719).

Akenside first offered the work to the publisher, poet, bookseller and dramatist Robert Dodsley (1703-64) in 1743, but he prevaricated until the work was approved by the great poet Alexander Pope (1688-1744), who provided the necessary reassurance that Akenside was “no everyday writer”.

Thomas Grey (1716-71), another poet of stature, was less fulsome in his praise, however, referring to Akenside’s finest hour as merely “above the middling”.

Akenside, as mentioned, was combative, and he had a spat with the critic and churchman William Warburton (1698-1779) over some of the content of The Pleasures of the Imagination. But while he ruffled some feathers, his epic poem did make him something of a celebrity.

He then returned to medicine, studying briefly at Leyden (Leiden) in the Netherlands, where he wrote a dissertation on embryology and obtained his diploma in 1744. During this period he befriended Jeremiah Dyson (1722-76), a rich and generous confidant who, in addition to bestowing on him the princely sum of £300 per annum, became a lifelong friend and loyal fighter of literary battles on Akenside’s behalf.

He also met the French philosopher Paul Heinrich Dietrich, Baron d’Holbach (1723-89) who went on to translate The Pleasures of the Imagination into French in 1759.

Returning to England, Akenside returned to combat, turning to satire with An Epistle to Curio (1744), prompted by the political about-face of William Pulteney (1684-1764), who professed Whig sympathies for years but then accepted the earldom of Bath from a Tory ministry.

Dyson remained a loyal friend and tried to open doors for his friend, but Akenside’s arrogance and pedantic behaviour tended to see them slam shut again. No matter, in 1745 he produced Odes on Several Subjects, and Dyson’s financial support enabled him to “keep a chariot”, (perhaps the equivalent of today’s urban SUV?) and “to live incomparably well”.

In 1746, he produced Hymn to the Naiads, which received its fair share of praise. He also produced To the Evening Star, and became a contributor to Robert Dodsley’s Museum, or Literary and Historical Register. In 1753, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Again, however, the medical profession called, and in the same year he was elected FRS he was admitted MD at the University of Cambridge, becoming a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians the following year (1754).

He gained a position as principal physician to Christ’s Hospital, London, but apparently his demeanour let him down again. He was particularly unkind to poorer patients and was upbraided for ‘harsh treatment.’ A change of monarch worked in his favour, however. When George III came to the throne in October 1760, Akenside ditched his Liberal principles and converted to Tory ideas (just as Pulteney had done in incurring Akenside’s wrath 15 years earlier). This about-face was soon rewarded by a new appointment – that of physician to the queen (Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, who had 15 children, so was probably in need of some medical attention) – which rather goes to show that you can’t keep a good man down, lousy bedside manner or not.

Mark Akenside died aged 48 on June 23, 1770, at his home in the fashionable London district of Mayfair, and was buried in St James’ Church, Westminster, so he ended up quite close to Parliament in the end. He never married, so left no children, but, somewhat unusually, has an asteroid – ‘8686 Akenside’ – named after him.

Although he was irascible, his friendship with Jeremiah Dyson was a true one and Akenside duly left his literary archive and personal effects to his longstanding pal. Dyson would repay him by publishing another volume of his poems in 1772, which included a revised version of The Pleasures of the Imagination which Akenside had been toiling over when he passed away.

Sadly, by the early years of the 20th Century, the works of Mark Akenside were largely neglected, but his name remains familiar in the city of his birth, thanks to Akenside Hill, and Akenside Terrace in Jesmond. He is also widely credited for influencing some notable names who followed him, including Coleridge, Wordsworth, Keats, and the artist JMW Turner.

Akenside House, Akenside Hill, Newcastle

Mark Akenside: A life

1721 Born in Newcastle on November 9

1737 Akenside’s first poetry is published, beginning with The Virtuoso

1738 A visit to Morpeth inspires Akenside’s great work, The Pleasures of the Imagination

1739 Akenside studies at Edinburgh University (until 1741), switching from theology to medicine

1744 Akenside’s magnum opus, The Pleasures of the Imagination, is published

1753 Akenside is elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS)

c.1760 He is appointed a surgeon to Queen Charlotte

1770 He dies in Mayfair, London on June 23, aged 48