The Boer roar

The Relief of Ladysmith by John Henry Frederick Bacon, depicts a meeting of the defenders and the relief column during the raising of the siege of Ladysmith on February 28, 1900. The caption to the oil painting reads: Sir George White welcomes Major Hubert Gough with these words, ‘Hello Hubert, how are you?’ Shortly afterwards, moved by the ovation given him by his soldiers and townsfolk, he acknowledged their support, ending with these words: ‘Thank God we have kept the flag flying’ (National Army Museum / www.nam.ac.uk)

First published in edition 196 of The Northumbrian, Oct/Nov 2023

As we approach Remembrance season, Stephen Roberts considers the Second Boer War and the region’s memorials to the fallen of that conflict, now well beyond living memory

The Second Boer War (1899-1902) ground to a halt on May 31, 1902, after 2½ years of bloody warfare. It was the last contested by British forces where more men died of disease than wounds, and the first for which memorials were erected en masse, the 1,000 or so in Britain a reflection of the number who fought, which on the British side was some 350,000.

It followed the First Boer War (1880-81) fought between Britain and the Afrikaners (the Boers) of South Africa; descendants of Dutch farmers (‘boer’ is ‘farmer’ in Afrikaans) who began settling there in the mid-17th Century.

Britain absorbed South Africa into its empire in 1806, prompting Boers to depart Cape Colony for the Transvaal, Orange Free State and, to a lesser extent, Natal. The Transvaal rebelled against the British government, winning a convincing victory at the Battle of Majuba Hill (1881) which led to Britain recognising Transvaal’s independence.

There were countless wars of empire during Queen Victoria’s reign, of which the First Boer War was a rare British reverse.

With the discovery of African gold and diamonds, there was talk of Britain ruling Africa from Cape to Cairo, but the truculent Boers were felt to be in the way, literally, so there had to be another reckoning. A spark for this second war was, arguably, the Jameson Raid of December 1895-January 1896; an ill-conceived, botched raid into the Transvaal designed to generate a rebellion of discontented Brits living and working there. It failed miserably, and as a result, the Boer hold on the Transvaal and its gold mines was strengthened rather than weakened.

An 1896 illustration depicting the arrest of Leander Starr Jameson after the failure of the Jameson Raid (Dec 29,1895-Jan 2, 1896) – the abortive invasion of the Transvaal which aimed to overthrow the Boer republic and one of the events that precipitated the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War, when it eventually broke out in October 1899, was fought on an altogether larger scale than the first. It followed failed attempts to resolve the status of the Transvaal’s British population – the so-called ‘uitlanders’ (foreigners) who mined gold, but were denied political rights.

The Boers moved against the British in Natal and the Northern Cape, laying siege to Ladysmith, Kimberley, and Mafeking, the latter gaining notoriety as the then longest siege in British military history (until Tobruk during World War II), and making Robert Baden-Powell (who went on to found the Scout movement) a national hero for its defence.

December 1899’s ‘Black Week’ saw major British defeats as the imperial power struggled to nullify an enemy of crack shots and exponents of ‘hit and run’, who struck and then disappeared into the Veldt. The Boers also gained a victory at Spion Kop in January 1900.

Haymarket, Newcastle, memorial

The 1st Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers formed part of the 9th Brigade which participated in the Battle of Modder River in November 1899 in a bid to relieve the siege of Kimberley. The 2nd Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers, meanwhile, joined the 1st Royal Scots and 1st Sherwood Foresters in another brigade, and both sets of fusiliers were involved in several battles. Hence the Northumbrian Regiments Memorial, also known as the South African Memorial, at the Haymarket in Newcastle.

Inscribed To the memory of the officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the Northumbrian regiments who lost their lives in the South African War, 1899-1902, erected by their county and comrades, it was designed by T Eyre Macklin RBA and unveiled on June 22, 1908 in the presence of Lt Gen Sir Laurence Oliphant KCVO.

It comprises a large stepped base topped by a plinth and a tapering hexagonal column climbing to a winged figure of Victory. The base features another figure, that of Northumbria, reaching towards Victory with a palm branch in memory of her fallen sons.

The plinth incorporates panels recording the names of 131 dead. The Northumbrian regiments mentioned are the Elswick Battery (1st Northumberland Volunteer Artillery), Newcastle Royal Engineers, Northumberland & Durham Imperial Yeomanry, and the Northumberland Fusiliers, whose men make up the majority.

Blyth’s Boer War Celtic cross is next to the town’s WWI memorial

(photo: Reading Tom, www.flickr.com)

In the north-west corner of Ridley Park in Blyth there is a Celtic cross on a tapering rectangular column commemorating six local men who died in the Second Boer War. Sitting next to the WWI memorial, it originally stood at the junction of Bridge Street and Freehold Street, moving to the park in 1950. Designed by Morrison and McLean of Gateshead, it was unveiled by Lord Ridley on July 22, 1903 at a ceremony also attended by Revd CW James, vicar of Blyth and chaplain of the Blyth Volunteer Corps. Its inscription reads: In memoriam, men of this district who fell in the Boer War 1899-1902, dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, this monument was erected by public subscription. The Latin in the inscription is a quotation from The Odes by the Roman poet Horace, in which it is claimed that, “it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country” – an assertion the World War I poet Wilfrid Owen would later describe as “the old Lie.”

Holywell in North Tyneisde’s Grade II-listed Boer War memorial – a round marble drinking fountain with a domed top surmounted by a ball supported by four slender pillars along with a horse trough – is unusual for its time and purpose. Also bearing a plaque to villagers who died in World War II, it was unveiled on July 12, 1901, when the Second Boer War was still in progress. Its inscriptions include some which must have been added after the unveiling, including one to Smith Bewick, who died from wounds received at Shoremans Drift, South Africa, 20th December 1901, in his 48th year; and William Coxon, who fell at the Battle of Rheinosterfonteine, South Africa, 5th September 1901, in his 22nd year.

Bellingham’s Boer War memorial (photo: Velodenz, Flickr)

Bellingham’s Grade II-listed memorial is of sandstone with a marble inscription panel and, like Holywell’s, doubles as a drinking fountain. A square canopy rests on four marble columns, sheltering the figure of a soldier with a stepped plinth and base below and a lamp atop the whole. Erected in honour of the following local members of Yeomanry and Volunteers who fought in the Boer War 1900-1-2, the memorial lists 33 names.

Alnwick’s Boer War memorial to the 5th Battalion the Northumberland Fusiliers is on the main column near the door of St Michael and St Paul’s Church. Unveiled on July 10, 1904 at a ceremony attended by the then Duke of Northumberland, honorary colonel of the regiment, the memorial is a rectangular wall-mounted white marble tablet with a red marble backboard. It lists 23 dead.

The statue of Elliott Benson in Hexham

Hexham’s Grade II-listed memorial at the southern end of Beaumont Street is more traditional – a soldier atop a plinth, which commemorates Lt Col George Elliott Benson, who died in the Battle of Bakenlaagte, October 30, 1901: To the memory of a gallant soldier, George Elliott Benson, who was born at Allerwash, 24th May 1861 … fell while commanding his column at the Battle of Bakenlaagte … he is buried with those who fought and died with him. The Unreturning Brave. A Royal Artillery colonel, the motto of the R.A is incorporated: Everywhere where right and glory lead. The monument is by John Tweed, assisted by Auguste Rodin, and was unveiled in 1904.

A memorial to a single person is atypical, but in Hexham Abbey a brass plaque remembers more, listing the men of the Hexham Volunteer Company, 1st Volunteer Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers. It was unveiled on September 3, 1905 and there are 47 men named on the plaque, of whom only five returned.

Tynemouth’s Boer War memorial is a sandstone pillar/column with bronze plaques at the western end of The Green (Front Street) which commemorates 19 dead. It has a stepped base, a plinth with decorative pillars and a column with decorative buttresses and a domed cap. Unveiled on October 13, 1903, the ceremony was attended by local clergy and dignitaries.

These memorials are testimony to the heavy losses inflicted on British forces during the war. For as it went on, more and more British troops were sent in in a bid to overwhelm the Boers with weight of numbers. Eventually, the policy worked and the tide turned, though not without loss.

The besieged towns were relieved, Mafeking after 217 days, and the British had taken Bloemfontein, Johannesburg and Pretoria by June 1900. Finishing off the Boers was difficult, however, their guerrilla tactics inflicting heavy losses on British forces. The response of Lord Kitchener (famous during WWI for those recruitment posters) was a scorched earth policy and camps for Boer women and children. Peace finally came in 1902, with the Boers forced to seek terms. The names on the region’s memorials testimony to those who would not return.

For more info, visit The Fusiliers Museum of Northumberland at Alnwick Castle, or its website at: www.northumberlandfusiliers.org.uk

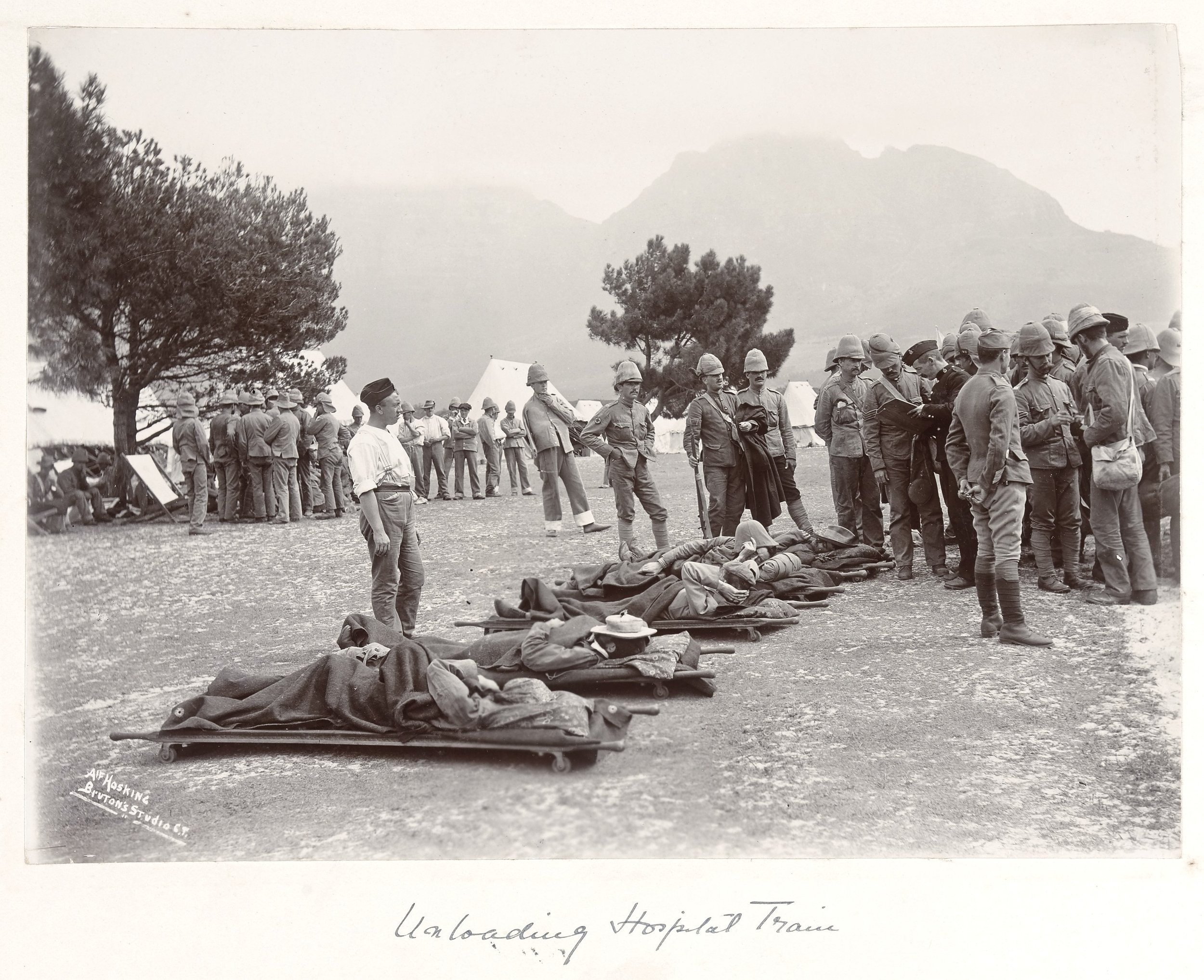

Wounded British soldiers unloaded from a hospital train during the Second Boer War (photo: Wellcome Images, the Wellcome Trust)